Saturated fat is a controversial topic. The current mainstream view is that saturated fat increases your risk of heart disease. This is reflected in the national guidelines to reduce your dietary intake of saturated fat.

Understanding what factors affect the risk of developing heart disease is extremely important, as heart disease is the number one killer across the globe.

As with most dietary policies, everyone assumes that there is rigorous evidence to back up the claims. This guide will examine the evidence and explain why the science behind the claim that saturated fat increases your risk of heart disease is weak.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

The logic behind blaming saturated fat

The reason why so many people believe saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease is because of the following two assumptions:

1) Saturated fat in the diet increases the amount of ‘bad’ cholesterol (also known as LDL cholesterol) in the blood

2) Higher levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol clog the arteries and lead to heart disease.

If ‘bad’ LDL cholesterol causes heart disease, and saturated fat in the diet increases LDL levels, then it logically follows that:

3) Saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease.

The two steps to this conclusion are widely accepted by many expert bodies. However, the problem with having multiple steps to reach a conclusion is that we need to be 100% certain that both assumptions are true and that (1) causes (2), rather than there simply being an association between dietary saturated fat and heart disease.

For example, yellow fingers are associated with lung cancer. But it is clear to us all that yellow fingers don’t cause lung cancer. However, if we didn’t know this and saw that most patients with lung cancer had yellow fingers, we might incorrectly conclude that yellow fingers cause lung cancer. This incorrect theory might then lead us to develop new techniques for managing yellow fingers (e.g. special soaps to remove the stains) while overlooking the true cause of lung disease (smoking).

Going back to heart disease, the question we need to ask is: do higher LDL (‘bad’ cholesterol) levels in the blood cause heart disease, or are they simply associated with heart disease?

For the two steps of the widely accepted heart disease theory to be true, there would need to be strong evidence that saturated fat intake directly increases the risk of heart disease. That is the focus of this guide because, at Second Nature, we don’t believe the evidence is strong enough.

Key points:

- The widely accepted view is that saturated fat from our diets leads to heart disease.

- For that to be true, there would need to be strong evidence that saturated fat increases cholesterol, and this leads to the arteries getting clogged and, ultimately, heart disease.

- The evidence doesn’t appear strong enough to support these claims.

How did dietary cholesterol get into the equation?

The human body is incredibly complex and difficult to study. Despite recent advances in science, exactly how the body works at a cellular level still remains a mystery. Often, we come to a conclusion (such as ‘saturated fat is bad for us’) through an educated ‘guess’, rather than solid physiological knowledge or understanding. These ‘guesses’ are then either supported or contradicted by evidence as science and research progress.

The idea that higher cholesterol levels caused heart disease was driven by Ancel Keys in the late 1940s. At this point, no one knew LDL (‘bad’ cholesterol) existed, so Keys was referring to total cholesterol. He became interested in the topic when he noticed that, surprisingly, American business executives, presumably among the best-fed people in the world, had high rates of heart disease.

Keys made an educated guess and proposed a link between blood cholesterol levels and heart disease.

To support his theory, he studied the population of Naples, which had the highest concentration of people in the world living past the age of 100. Keys suggested that a Mediterranean-style diet that was low in animal fat protected against heart disease, and conversely, that a diet high in animal fat led to the condition.

His theory was further explored in what has become famously known as his Seven Countries Study. This study seemed to show that blood cholesterol levels were strongly related to heart disease and the higher the blood cholesterol levels, the higher the risk of heart disease.

Keys went on to create a scientific equation to predict the effect of saturated fats in the diet on blood cholesterol levels. This equation also included the impact of dietary cholesterol on blood cholesterol levels. To summarise part of the equation:

· Higher levels of saturated fat and cholesterol in the diet would increase blood cholesterol levels

As a result, representatives of the American Heart Association appeared on television in 1956 to inform people that a diet high in butter, lard, eggs, and beef would lead to heart disease.

This is where the low-fat and low animal-fat messaging first originated, and it resulted in the American government officially recommending that people adopt a low-fat diet to prevent heart disease. This advice followed suit internationally.

Since then, pharmaceutical organisations, research institutions, and charities have spent billions of dollars trying to reduce blood cholesterol levels and hopefully solve heart disease. The idea that cholesterol causes heart disease became firmly established.

Key point:

- Ancel Keys made an educated guess and proposed a link between saturated fat, blood cholesterol levels, and heart disease.

- An observational study called ‘the Seven Countries Study’ appeared to support this idea.

Changes to the equation

Keys’ heart disease equation started with the theory that dietary cholesterol (e.g. from eggs) would affect blood cholesterol levels. This was soon discarded after an experiment where Keys fed eggs to volunteers (eggs contain more cholesterol than any other food) and found that their cholesterol level did not change.

It’s now widely accepted that cholesterol in the diet has no significant impact on blood cholesterol levels. In 1997 Keys wrote this:

‘There’s no connection whatsoever between cholesterol in food and cholesterol in the blood. And we’ve known that all along.‘

More recently, the fact that cholesterol in the diet has no impact on blood cholesterol levels or heart disease was reaffirmed. In 2015, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee in the USA, having reviewed all the evidence made this statement:

‘Cholesterol is not considered a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.’

So overconsuming cholesterol isn’t something we need to worry about in relation to heart disease, but what about saturated fat?

Key points:

- After his own experiments, Keys noted that there was actually no link between dietary cholesterol and cholesterol in our blood.

- Then, saturated fat was seen as the remaining cause of heart disease.

The link between saturated fat and heart disease

We discussed how Keys had demonstrated that blood cholesterol levels were strongly related to heart disease from his Seven Countries Study. However, what people didn’t know at the time, and has since been shown, is that the 7 countries chosen for Keys’ study were handpicked in advance as they were more likely to align with the cholesterol and heart disease theory. Other countries that might conflict with that hypothesis, such as France, had been left out.

So cracks begin to show in the theory that saturated fat causes heart disease, as the evidence was distorted.

Since then, multiple large-scale analyses (called ‘meta-analyses’) have been conducted on large populations that have been followed carefully for decades, examining what they eat and what they die of. All show no consistent association between dietary saturated fat intake and risk for heart disease or death from all causes.

In fact, some of these studies show the opposite; an inverse association of dietary saturated fat intake and heart disease.

A number of these studies also suggest that the risk of heart disease increases when dietary saturated fat is reduced and replaced by carbohydrate.

Key points:

- Countries that didn’t agree with Keys’ theory appear to have been left out of the Seven Countries Study.

- Since then, large-scale analyses have shown no consistent link between saturated fat intake and risk for heart disease.

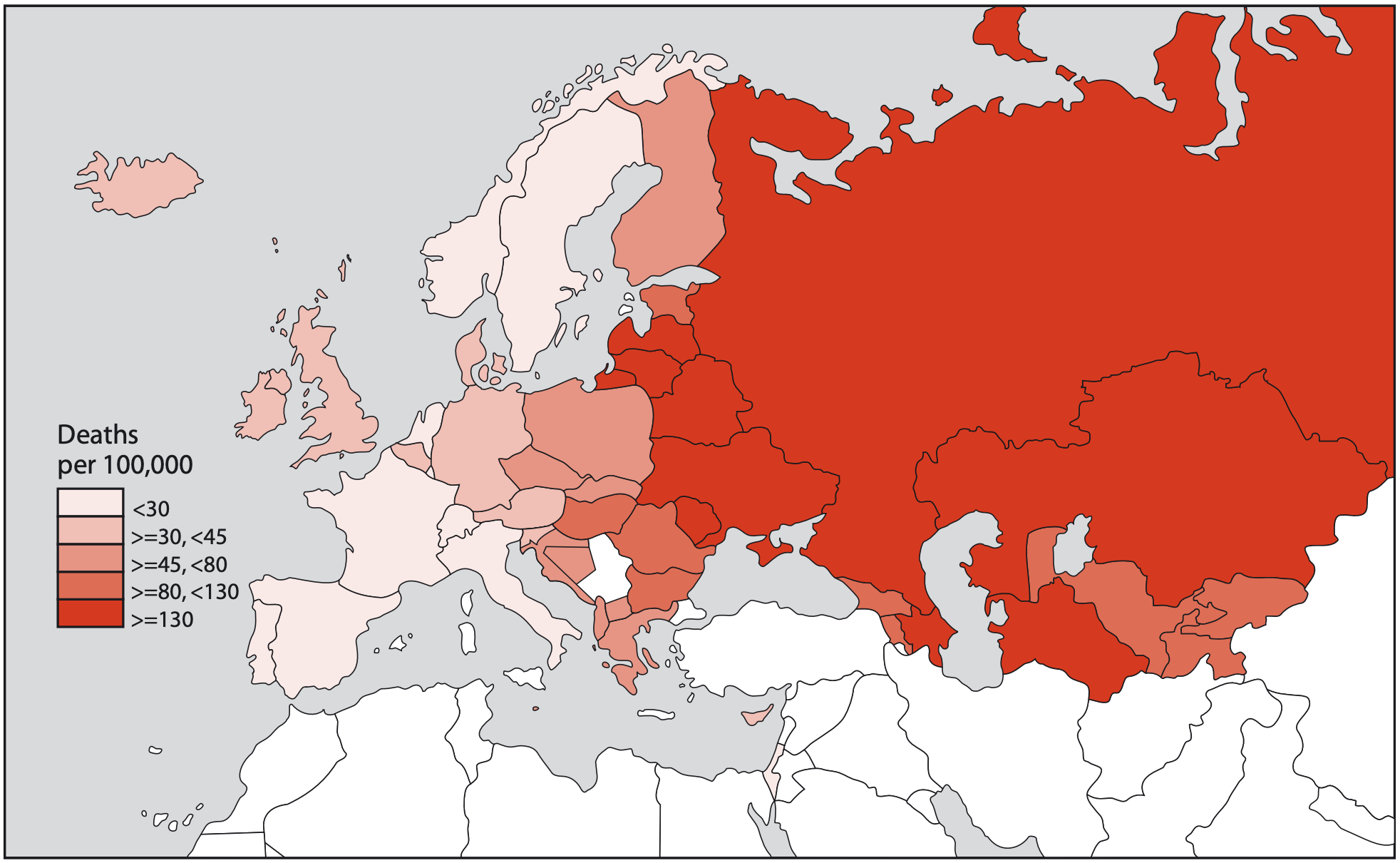

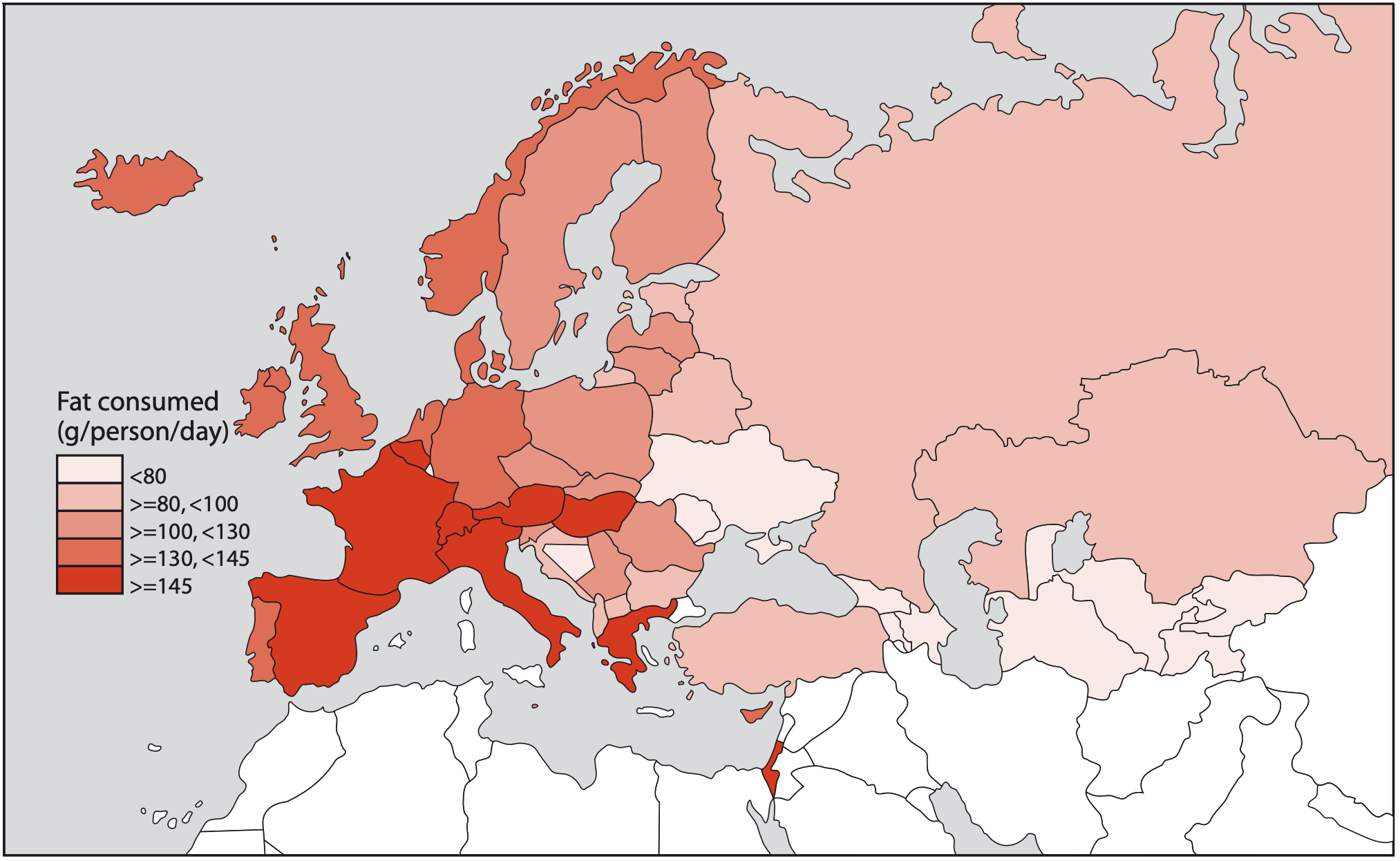

Countrywide evidence

Looking at the rates of heart disease in countries that weren’t handpicked for Keys’ study can shed light on the saturated fat debate.

A publication by the British Heart Foundation – using data from the World Health Organisation – showed two very different pictures:

1) Deaths per 100,000 from heart disease. Dark red means a high level of deaths

2) Average fat levels consumed per day. Dark red means a high level of fat consumption

As you can see in picture 1), deaths from heart disease show a clear gradient from light red to dark red as you go from west to east (Russia having the highest rates). Picture 2) shows the exact opposite trend; higher fat consumption in the west and decreasing to the east.

The same publication also provided data on the saturated fat intake of different countries and the corresponding heart disease deaths:

| Country | Saturated fat intake (% of all energy intake) | Heart disease deaths per 100,000 people, per year (men under 65) | Blood cholesterol levels |

| Georgia | 5.2% | 235 | 5.0 mmol/l |

| Azerbaijan | 5.7% | 219 | 5.0 mmol/l |

| Ukraine | 7.6% | 208 | 5.1 mmol/l |

| Russia | 8.3% | 267 | 5.1 mmol/l |

| Israel | 8.6% | 44 | 5.6 mmol/l |

| Spain | 10.9% | 33 | 5.6 mmol/l |

| Italy | 11.8% | 36 | 5.9 mmol/l |

| UK | 13.5% | 76 | 6.0 mmol/l |

| Switzerland | 15.3% | 32 | 6.4 mmol/l |

| France | 15.5% | 24 | 5.9 mmol/l |

What you can see from this data is that as saturated fat intake increases, heart disease deaths go down. A complete opposite trend to what the cholesterol theory suggests. You’ll also notice that as average blood cholesterol levels increase, heart disease rates also decrease (similarly, opposite to the cholesterol theory).

So, we might question why the British Heart Foundation hasn’t reconsidered its recommendations around saturated fat intake, despite publishing this data. A potential answer is that the report is 188 pages long and the picture and data tables were found at opposite ends of the report.

Key points:

- Countrywide evidence shows an opposite trend to what the cholesterol theory suggests.

- As dietary saturated fat and blood cholesterol levels go up, deaths from heart disease appear to go down.

- This evidence weakens the saturated fat and cholesterol theory.

Take home message

The widely accepted view that cholesterol levels are linked to heart disease is based on the assumptions:

1) Saturated fat in the diet increases the amount of ‘bad’ cholesterol (also known as LDL cholesterol) in the blood

2) Higher levels of ‘bad’ cholesterol clog the arteries and lead to heart disease.

Therefore:

3) Saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease.

However, as this guide has shown, the evidence for the third claim is weak. Not only do recent large meta-analyses show that there is no association between saturated fat intake and heart disease, but there is also plenty of data showing the opposite trend.

Whilst we are not suggesting that saturated fat reduces the risk of heart disease, we don’t believe there is sufficient evidence to conclude that saturated fat intake increases the risk of heart disease. In our guide around cholesterol and heart disease, we explore step 2) of the widely accepted cholesterol theory.