Myth Busting

Is exercise more important than diet?

Written by

Tamara Willner

Medically reviewed by

Dr Rachel Hall (MBCHB)

Principal Doctor

5 min read

Last updated February 2026

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Myth: ‘If I exercise then it doesn’t matter what I eat.’

Many individuals have an unhealthy diet, high in ultra-processed food and sugar, but think it doesn’t affect their health since they engage in regular exercise. Is there any truth behind the myth that physical activity and diet can cancel each other out? The short answer is no.

Does weight equate to health?

The myth stems from the general misconception that being thin, or within the national healthy BMI range, equates to being healthy. Just because someone might be able to eat ‘unhealthy’ food and not gain body weight, this does not mean that they are metabolically healthy.

Research suggests that up to 40% of people within the healthy BMI range show signs related to metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a term that describes a combination of disorders, including type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity.

To illustrate that you cannot always judge health based on body size, take individuals with lipodystrophy (a condition where your body isn’t able to make or store fat). These people still experience insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver disease.

Key point:

- Being thin does not mean you are metabolically healthy.

- Isn’t it simply calories in = calories out?

Isn’t it simply calories in = calories out?

Usually, people who think you can outrun a bad diet believe ‘calories in = calories out’ (frequently abbreviated to CICO). Thinking like this, it doesn’t matter whether you use up calories in exercise or reduce your energy intake.

However, not all calories provide equal benefits. Eating too many refined carbohydrates, for example, can lead to high blood sugar and promote fat storage. On top of this, protein and fat are digested more slowly than carbs, which means they leave us feeling fuller for longer. This reduces the chances of snacking and feeling hungry or deprived.

Another reason to question this theory is that it would take an extremely long time to ‘exercise off’ foods we eat. For example, in a normal-sized Cadbury’s dairy milk chocolate bar there are 240 calories. For an average, moderate-intensity workout in the gym it could take 30 mins – 2 hours to use up this many calories, depending on your size and the type of exercise you are doing.

We also use up a certain amount of energy each day at rest on basic functioning, for example, breathing and circulation. This is called our basal metabolic rate (BMR) and is different for everyone, depending on body size, age, gender, and genetics. So even when we are not exercising, our body does burn some energy.

However, according to CICO, we would still have to exercise at a high-intensity for a very long period each day to use up more calories than we eat. This is obviously impractical.

Key points:

- Thinking that you can ‘cancel out’ food with exercise doesn’t make much sense.

- Not all calories provide equal benefits.

- It takes a long period of high-intensity exercise to use up a significant amount of calories.

Does exercise help with weight loss?

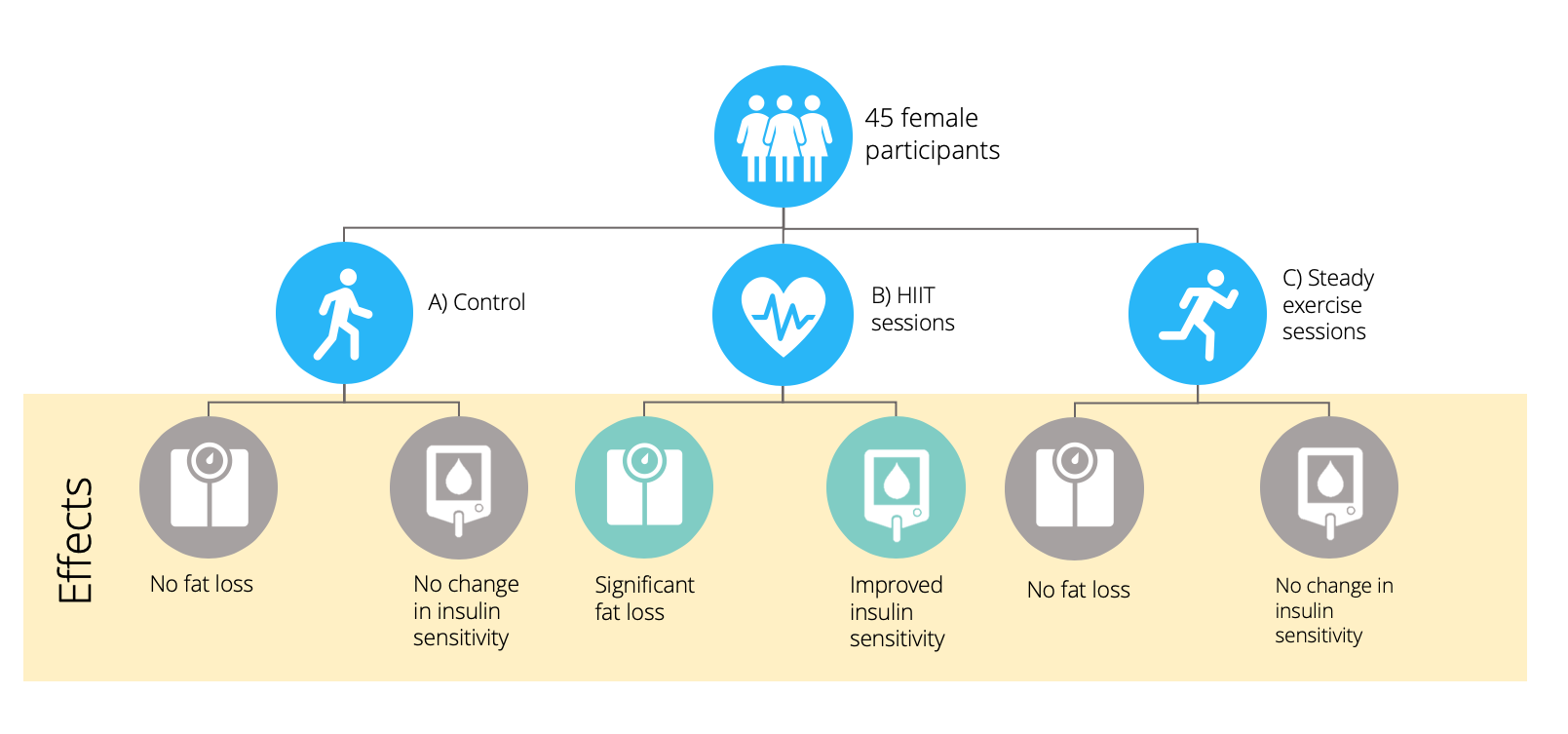

This is a complex question and in short, the right type of exercise can aid weight loss. In our guide on finding the time to exercise, we discussed a study that compared high-intensity exercise to longer steady exercise. Results demonstrated that those in the high-intensity group lost significantly more fat than those in the steady exercise group.

In this study, their diet was controlled, so it is likely that the differences in weight were down to the differences in exercise. The researchers suggested that high-intensity exercise has a positive impact on certain stress hormones released by the kidney that accelerate fat oxidation.

The current national guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise is a rather arbitrary number. It should be used as an encouragement to keep moving, rather than signposting the required amount of exercise for weight loss. As discussed, high-intensity exercise is more likely to help with weight loss than moderate or low-intensity exercise.

Key points:

- Exercise has many benefits.

- If weight loss is your goal, high-intensity exercise is best.

Will exercise improve my health then?

Other than weight loss, there are a number of benefits to exercise. Exercise of any intensity can help to improve your blood sugar control, heart health, and mental health.

All of these factors contribute to your overall health and protect against metabolic syndrome. As we have already discussed, being ‘thin’ does not equate to being metabolically healthy.

Are diet and exercise both necessary for health?

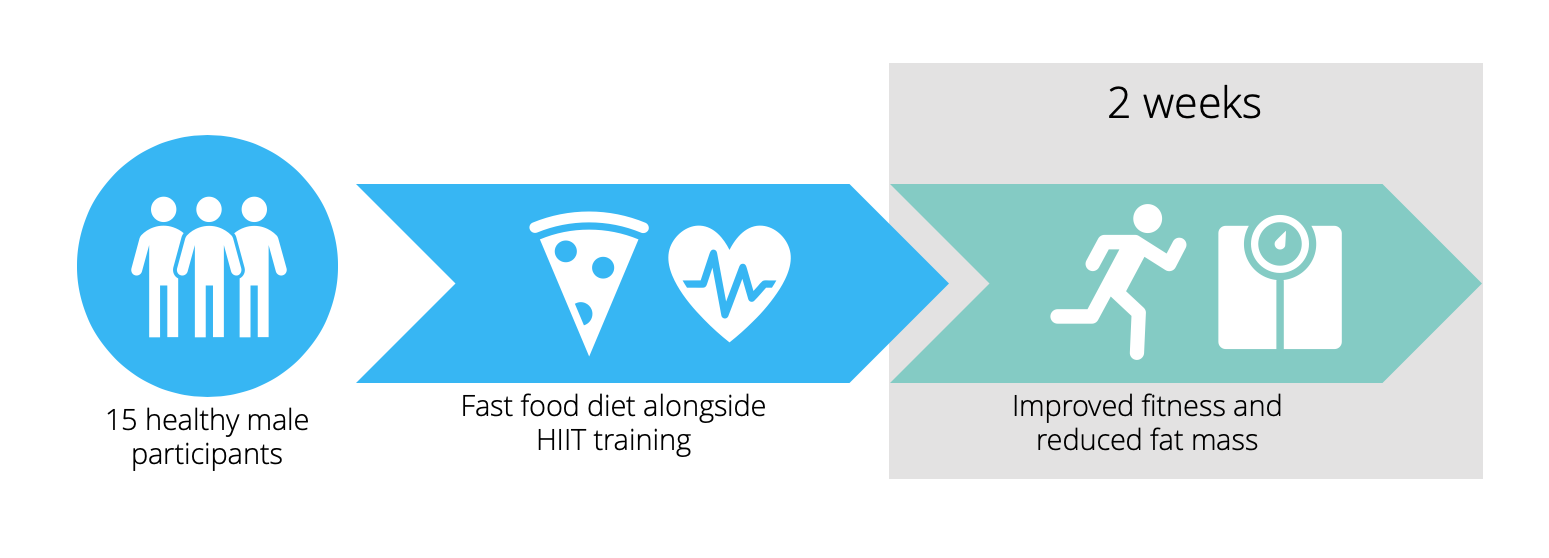

The difficulty with this statement is that not much research exists that examines it. One study restricted 15 male participants to a fast-food only diet for 2 weeks, alongside daily high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

Surprisingly, results showed improvements in fitness and a reduction in fat mass. This seemingly supports that idea that we can be healthy if we exercise but do not eat well, however, when we examine the study further it breaks down.

Firstly, participants were healthy, young males, which means that at the start of the trial they were metabolically healthy. 2 weeks is not a long enough period of time to see significant changes in metabolic health if someone is already metabolically healthy.

On top of this, there was no control group who were not exercising to compare. With no comparison, we cannot say for sure that it was the exercise that ‘outran’ the unhealthy diet.

Longer studies that compare groups eating fast-food diets with and without exercise are necessary. Although it becomes an ethical dilemma when we think about exposing individuals to an unhealthy diet for a long period of time.

Anecdotal evidence of athletes who develop chronic conditions suggests that diet and exercise are both important for health. For example, Steve Redgrave, a British rower who won 5 Olympic gold medals. After many years of consuming a 7,000 calorie per day high-sugar diet, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Although the specific cause is not certain, it is quite likely that prolonged high blood sugar, as a result of eating excessive carbohydrates, contributed to the development of type 2 diabetes.

Overall, there is little quality evidence available as to whether you can be healthy if you exercise often but do not eat well. However, the evidence that diet and exercise can individually impact your metabolic health suggests that both are necessary pieces of the health puzzle. Moreover, exercise has a huge positive impact on your mental health and should not be viewed solely as a way to counter an unbalanced diet.

Key points:

- There is little good evidence exploring whether you can be healthy if you exercise but have a poor diet.

- Some anecdotal evidence suggests that a poor diet is not counteracted by exercise.

- Overall, evidence suggests both a healthy diet and exercise are necessary to be metabolically healthy.

Take home message

- Evidence suggests overall that your diet is equally important to exercise.

- Some individuals maintain a BMI within the ‘healthy’ range but are metabolically unhealthy.

- Being thin does not equate to being healthy.

- Exercise and healthy eating provide different benefits and work together to keep you healthy on the inside and outside.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Download our free, indulgent 7-day meal plan

It includes expert advice from our team of registered dietitians to make losing weight feel easier. Subscribe to our newsletter to get access today.

You might also like

As seen on

As seen on