We spend one-third of our lives sleeping. The longest a human has ever gone without sleep is only 11 days. It’s clear that sleep is important, but just how essential is it and what happens to our bodies when we don’t get enough sleep?

Research has explored sleep and why it features in the daily cycle of almost every animal on earth (apart from baby dolphins). It doesn’t make sense from an evolutionary perspective. If you were an animal prone to predation, why would you leave yourself in such a vulnerable state every single night (or day) of the year?

The exact function of sleep is still a slight mystery, but it significantly impacts different aspects of our mental and physical health. Yet, we live in a chronically sleep-deprived society.

Between work, children, studies, hobbies, exercise, and social events it can seem impossible to build a regular sleep pattern and consistently get a good night’s sleep. This is a severe problem! We have written a separate guide on how to sleep better, which includes how much sleep is enough, what counts as quality sleep, and tips on how to improve your sleep.

Epidemiological studies stress the importance of sleep and all point towards the same idea: the shorter (and the worse quality) your sleep, the shorter your life. But what does sleep actually affect?

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Weight loss

You might notice that, if you’ve had a miserable night’s sleep, you’ll have stronger food cravings and less willpower to resist unhealthy snacks. Is this just an illusion or is there a scientific explanation?

Well, scientists are starting to understand better why poor sleep results in weight gain.

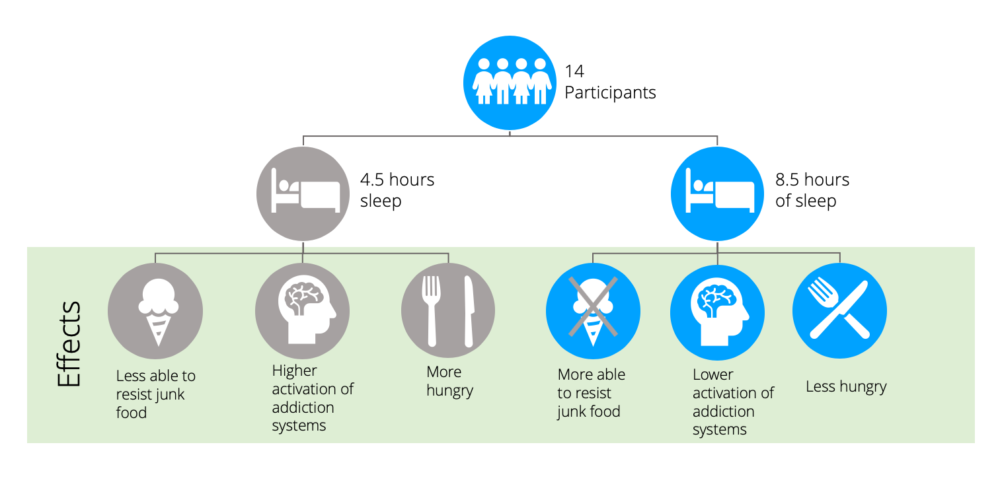

A recent scientific publication showed that, when people had at least 8.5 hours of sleep, the part of their brain that controls feeding and appetite had a very low level of activation. They were less hungry, had a lower energy intake, and lower activation of their reward and addiction systems in their brain.

When the scientists reduced the participants sleep to 4.5 hours, participants reported increases in hunger and appetite. In addition, they were more likely to choose snacks with 50% more calories than the people with 8.5 hours of sleep.

Finally, the sleep-deprived people were unable to resist what the researchers called ‘highly palatable, rewarding snacks’ (meaning cookies, ice cream, and crisps) even though they had consumed a meal that supplied 90% of their daily caloric needs two hours before.

So, sleep deprivation does indeed have a real effect on your desire and cravings for food, increasing your energy intake beyond what is required and increasing your hunger levels.

On top of this, research has shown that sleep loss decreases energy expenditure in two ways. First, and more intuitively, physical activity significantly decreases on the day following sleep deprivation.

Secondly, a study demonstrated that after total sleep deprivation metabolic rates of healthy men declined, which led to less energy expenditure. Although this second study does not tell us the effect that prolonged periods of partial, rather than total, sleep deprivation has on energy expenditure, it does show that disruptions in the sleep cycle can lead to the adaptive response of conserving energy.

The combined effect of increased energy intake and decreased energy expenditure demonstrates how a lack of sleep could facilitate weight gain or prevent weight loss.

Key points:

- Poor sleep can lead to weight gain, or prevent weight loss, by increasing your cravings.

- When we’re tired, we’re more likely to choose high energy junk foods, like biscuits.

- A lack of sleep also makes you expend less energy by reducing physical activity and resting metabolic rate.

Immune system

When we’re hit with a bad cold or flu our first instinct, as humans, is to curl up in bed and rest. Even as we try to resist by dosing up on day nurse and carrying on with our day, the drive to sleep remains.

In a podcast on ‘why we sleep’, Professor Matthew Walker explains that infection indicates to the immune system that we’re under attack, which in turn signals we need more sleep.

When we sleep, our autonomic nervous system, which comprises both a ‘fight’ or ‘break’ mode, is shifted into ‘break’ mode by deep sleep. In ‘break’ mode our heart rate decreases, cortisol (the stress hormone) decreases, and our body goes into immune stimulation mode. During this process, our immune army restocks, and we can fight infection better.

On the flip side, being sleep deprived can stress our immune system. Professor Walker noted that those who are sleeping 5 hours per night are four times as likely to catch a cold than those people sleep 8 hours.

A fascinating study demonstrated that just one night of sleep deprivation in healthy individuals results in a 70% drop in natural killer cells. Natural killer cells are like immune assassins that attack cancer cells, which naturally appear in your body every day, and fight infection.

So, we need an adequate amount of sleep to support our immune system in fighting infections and perhaps even in preventing cancer! What about other chronic diseases?

Key points:

- Sleep is a chance for our immune system army to recover and restock.

- Being sleep deprived makes our immune system weak and leaves us prone to colds and infection.

- Sleep deprivation reduces natural killer cells (which attack cancer cells).

Chronic disease

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is characterised by high blood sugar. Uncertainty about the cause of type 2 diabetes stems from whether insulin resistance (where our body does not respond to insulin) causes weight gain or vice versa. More recently, research has established a link between sleep and type 2 diabetes.

An extensive systematic review and meta-analyses, which included data from 10 different studies, demonstrated that quantity and quality of sleep consistently and significantly predicted the risk of type 2 diabetes. Although establishing a link, this observational data cannot determine that poor sleep was the actual cause of an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

A clinical trial investigated whether sleep can directly increase the risk of type 2 diabetes. For five nights, healthy young men were restricted to 4 hours of sleep. The result was impaired glucose metabolism and increased levels of insulin in the blood, suggesting that an insulin resistant-like state was induced.

On top of this, the men exhibited higher cortisol levels in the afternoons and evenings following the sleep restriction intervention, which has been shown to contribute to age-related insulin resistance.

The combination of short-term intervention and long-term observational evidence linking poor sleep to type 2 diabetes risk suggests that the quality and quantity of sleep plays a vital role in the prevention of this condition.

Key points:

- Short-term sleep deprivation leads to impaired glucose metabolism and increased insulin levels in the blood in healthy individuals.

- Combined with long-term observational evidence, research suggests that quality and quantity of sleep is an important factor in the prevention of type 2 diabetes.

Heart disease

A thought-provoking study, published by the British Medical Journal, noted that for 3 consecutive years, there was a 24% increase in heart attack hospital admissions following the spring daylight savings time change. Interestingly, the opposite happened after the autumn daylight savings time change, with a 21% reduction in heart attacks.

This data is by no means evidence for daylight savings causing or reducing heart attack rates, but it does demonstrate how sensitive we are to losing even 1 hour of sleep.

Research suggests that even modest daily sleep restriction in healthy people results in increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (substances secreted by immune system cells) IL-6 and TNFα. These cytokines are signals of inflammation in the body and are strongly associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and related death.

In his book entitled ‘Why We Sleep’, Professor Walker argues that deep sleep (the stages before rapid eye movement [REM] sleep) is one of the best forms of blood pressure medication. During deep sleep, our heart rate drops and blood pressure lowers, as previously mentioned. Simultaneously, a variety of restorative chemicals and hormones are released, including a particular growth hormone that helps to restore cells. This process, Professor Walker explains, is the ultimate TLC that the cardiovascular system could ask for.

Key points:

- Sleep restriction has been shown to increase inflammation in the body, which is strongly associated with heart disease.

- Sleep acts as a break for the cardiovascular system, as our heart rate decreases and blood pressure lowers when we sleep.

Alzheimer’s disease

It’s extremely common for individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease to experience sleep disorders. The prevalence of patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and cognitive impairment who experience sleep problems can reach as high as 54%.

An interesting theory is that the relationship between sleep problems and Alzheimer’s is actually a self-fulfilling cycle. This theory sprang out of a mice study that demonstrated a 10-20% increase in the flow of a fluid in the brain, called cerebrospinal fluid, during deep sleep.

Cerebrospinal fluid is thought to act as a brain cleanser, removing harmful waste products that build up if left untouched. One of these toxic waste proteins is called beta-amyloid. When beta-amyloid is left to build up over a long period, it can form amyloid plaques; a prominent feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Ironically, the area of the brain where beta-amyloid builds up is the same area of the brain that generates the deep sleep needed to flush it out. So, there we have it – a self-perpetuating cycle of sleep problems, amyloid plaque accumulation and more sleep problems!

A study tested this idea by depriving humans of deep sleep, but not total sleep. This is possible by playing a specific noise at a tone that lifts you out of deep sleep but doesn’t wake you up. A sample of cerebrospinal fluid, which circulates the brain and spine, was taken and measured for amyloid. After just 1 night there was a striking 25-30% increase in amyloid.

More evidence is needed, but it seems like consistently getting enough good quality sleep could help prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Of course, other factors are at play, such as genetics.

Key points:

- There is a strong link between Alzheimer’s disease and sleep problems.

- New research suggests sleep problems could contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease rather than be a consequence.

- When we sleep, cerebrospinal fluid flushes away waste products in our brain.

- One of these waste products, beta-amyloid, is a prominent feature of Alzheimer’s disease.

Memory and motor skills

Considering the theory discussed above of how sleep and Alzheimer’s disease are linked, it’s not surprising that there is a wealth of evidence suggesting that good sleep is necessary for memory formation and consolidation.

A pilot study investigated the effect of sleep deprivation on the ability to form new memories. Participants were split into sleep deprivation or normal sleep and then presented with positive, negative, and neutral words to remember. Overall, the sleep-deprived people demonstrated a 40% reduction in the ability to form new memories of all words.

Those who had slept as usual could remember positive and negative words better than neutral ones, which is expected as emotion often helps us encode new memories. Interestingly, those who were sleep deprived had particular difficulty remembering positive words. These findings suggest that sleep deprivation could lead to a higher proportion of memories linked to negative emotion.

A thorough review, published in the Annual Review of Psychology, concluded that both REM and non-REM sleep play a significant role in consolidating declarative memories (facts), especially those with an emotional link.

In a different review, procedural memory (how to do things), including auditory, visual, and motor skill learning, appeared to be sleep-dependent.

Part of procedural memory is learning motor skills, which are movements and actions of our muscles, such as walking or using a pen. Evidence tells us that we continue to improve our motor skills even after the practice has ended. A study demonstrated that this improvement after practising a motor skill depends on sleep.

Participants trained to do a finger-tapping task, either in the morning or the evening, all showed improvement following a good night’s sleep but not after 12 hours of forced wakefulness. This suggests that improvement in motor skills are not merely down to time passing by but rather sleep plays a role in consolidating these skills!

Key points:

- Sleep appears to impact our ability to remember words and facts, especially those associated with positive emotions.

- Sleep also seems to impact the consolidation of motor skills over time (remembering how to do certain actions).

Mental health

The automatic response to young children having tantrums is that they might be overtired and need a nap. Similarly, us adults seem to experience increased irritability and aggressive behaviour following a lack of, or inadequate, sleep. Interestingly, the importance of sleep for mental health may be more than merely feeling cranky after a bad night.

Professor Walker points out, in the previously noted podcast, that there is no psychiatric condition out there where sleep is undisturbed. In the past, psychiatric conditions were seen to result in sleep problems, but evidence has emerged suggesting it’s a two-way street.

This area of research is in its infancy, but if chronically disrupted sleep is a cause, rather than a consequence, of mental health issues such as major depression, it could have serious clinical implications.

Supporting this, when we look inside the brain, using fMRI scans, even healthy individuals who are deprived of just 1 night of sleep demonstrate a 60% increase in reactivity in the area of our brain that generates strong emotions, called the amygdala.

As well as emotional stability, research suggests that our social skills suffer from sleep deprivation. A study demonstrated that emotional empathy (our ability to recognise and respond to other peoples’ emotions) significantly decreases after sleep restriction. The result is that we might struggle to feel sympathy and compassion when we’re overtired.

Key points:

- As well as being a consequence, sleep might actually contribute to psychiatric conditions.

- Sleep deprivation also reduces our social skills and ability to sympathise with others.

Take home message

- Sleep impacts nearly every aspect of our physical and mental well-being.

- Sleep plays a significant role in weight loss, and lack of sleep can lead to weight gain by indirectly increasing our energy intake while reducing our energy expenditure.

- Evidence suggests that sleep is vital for proper immune function.

- Sleep deprivation increases risk factors for type 2 diabetes, such as impaired glucose metabolism.

- Following a lack of sleep, our bodies exhibit an increase in inflammation, which is strongly linked with heart disease.

- Recent evidence shows a place for sleep in cleansing our brains of toxins that build up each day, a process which may prevent the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Research demonstrates that sleep helps us consolidate both declarative (facts) and procedural (actions) memories.

- A lack of sleep increases activation in the areas of our brain that controls strong emotion and reduces our social skills.