Recent high-quality research suggests that red meat doesn’t adversely affect cancer risk. Nonetheless, red meat—such as beef, lamb, and pork—and its role within a healthy diet has been widely debated in the media.

It’s an excellent source of protein, vitamins, and minerals and is naturally low in carbohydrates. But recent media coverage has suggested that too much red and processed meat is linked with cancer, which has left many questioning whether they should continue to eat it. This guide will examine the science behind the headlines and put the research findings into context.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Where do the concerns come from?

Animal and test tube (in vitro) studies have suggested that high doses of certain chemicals found in red meat may have cancer-causing (carcinogenic) effects. However, the doses used in these studies are far higher than the amounts we’re typically exposed to through food. Plus, we can’t translate these findings to human health until further human trials are conducted.

Some observational studies show that red and processed meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of cancer. The findings are mainly related to bowel cancer (sometimes referred to as colon or rectal cancer), which is the fourth most common type of cancer in the UK.

Observational studies can, at best, suggest an association (or correlation) between two variables. It’s important to note that an association between two variables doesn’t provide evidence that red and processed meat causes cancer. Despite this, findings from nutrition observational studies are often misreported or greatly exaggerated in the media.

One observational study of 478,040 participants who were followed for an average of five years found that people who ate high amounts of red and processed meat (more than 160g per day-equivalent to one large beef burger patty) had a higher risk of bowel cancer compared to those with low intakes (less than 20g per day-equivalent to one meatball).

For each additional 100g of red and processed meat consumed, the researchers suggested that there was a 19% increased risk of bowel cancer. This is a very small increase in risk when compared to relationships which we know are causal (e.g. 10,000% increased risk of lung cancer amongst smokers).

In 2011, a report was published by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN); a panel that advises government organisations on nutrition. Based on findings from mostly observational studies, they concluded that both red and processed meat should be limited to 70g per day (cooked weight), which is equivalent to half of a large burger patty, to help prevent the risk of bowel cancer.

Shortly after, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reviewed the evidence for potential cancer-causing effects of red and processed meat. They assessed over 800 epidemiological studies (a type of observational study that investigates the distribution, patterns, and causes of diseases in populations) and concluded that current evidence suggests that red meat is a ‘possible carcinogen’ and processed meat is a ‘definite carcinogen’.

Key points:

- Most of the concerns about red meat and cancer refer to bowel cancer.

- The concerns are mainly based on findings from observational studies, which don’t tell us much about causation.

Current guidance on red meat consumption

Based on the SACN report mentioned above, the UK Department of Health suggests that people who eat a lot of red and processed meat (more than 90g per day) should eat no more than 70g per day.

This is equivalent to:

- One-third of an 8-inch sirloin steak

- Five tablespoons of minced beef

- Half of a large burger patty.

If we eat more than 90g on a particular day, the guidelines encourage us to eat less on subsequent days or have several meat-free days.

In 2018, the World Cancer Research Fund recommended that we should ‘eat no more than moderate amounts of red meat, and little if any, processed meat.’ They state that if we do eat red meat, we should eat no more than three portions (or around 350–500g of cooked meat) per week. This is equivalent to one 7oz rump steak and one serving of bolognese sauce per week.

It’s important to mention that national nutrition guidelines are constantly changing and are dependent on lots of factors.

Key points:

- Current UK government recommendations encourage people to eat no more than 70g of red and processed meat per day.

- These recommendations are based on findings from the 2011 SACN report.

The science behind the headlines isn’t clear-cut

Our risk of developing cancer is affected by many different factors, some of which we can’t change, such as our age or genes. We have greater control over environmental risk factors such as our physical activity levels and the food that we eat, but it can be difficult to identify how much of an influence a risk factor has on the risk of developing cancer.

Observational studies can help to provide evidence of associations between an exposure (e.g. eating red meat) and a disease outcome (e.g. developing cancer). However, they can’t determine that eating red meat was the actual cause of a person developing cancer.

Other limitations of observational research within this area are listed below:

- They don’t always account for other factors that could influence a person’s cancer risk (i.e. fruit and vegetable intake, smoking, or alcohol intake). These confounding factors can sometimes bias our results, leading us to make the wrong conclusions.

- They’re often reliant on people remembering what they ate in the past, which could result in inaccuracies.

- They don’t differentiate between processed meat and unprocessed red meat. Eating ultra-processed hot dogs and hamburgers is not nutritionally equivalent to eating high-quality, grass-fed beef steak.

Higher-quality studies have found that the association between red meat and cancer is weak and inconsistent. For example, one meta-analysis found a weak association in men but no association in women.

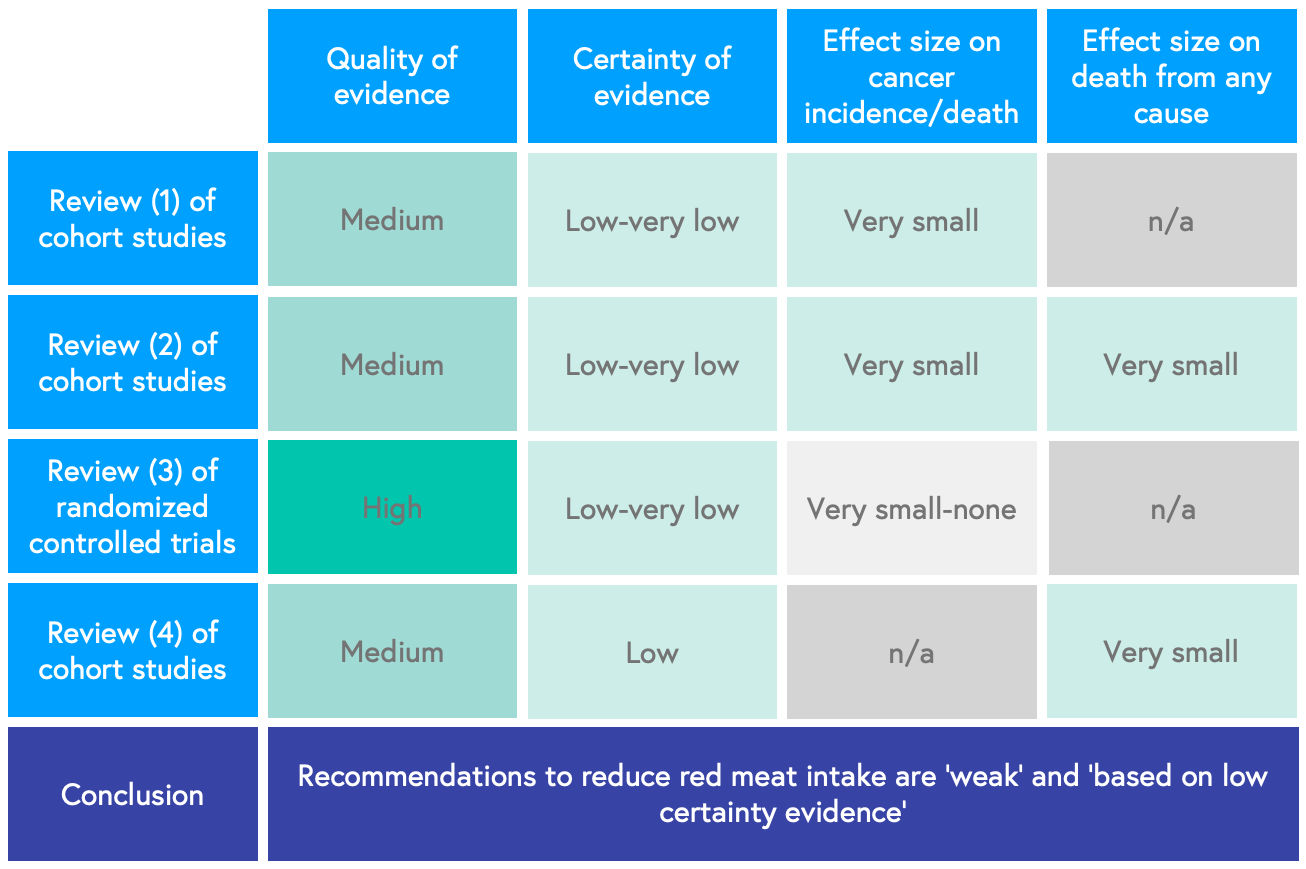

On top of this, a very recent study published in November 2019 has further challenged current public health recommendations by suggesting that adults don’t need to reduce their intake of red or processed meats, as these are ‘weak recommendations based on low-certainty evidence’.

The panel of 14 global experts conducted five systematic reviews , 4 of which examined the evidence on red and processed meat in relation to diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. In one particular study, they included 12 randomised controlled trials (gold-standard clinical research) before concluding that cutting down on red meat may have little or no effect on cancer mortality and incidence.

When we put everything together, these higher-quality studies suggest that eating unprocessed red meat doesn’t adversely affect cancer risk.

Key points:

- Observational studies are weak types of scientific evidence that can, at best, suggest associations between two variables.

- When examining the effects of meat on the disease risk, it’s important to differentiate between processed and unprocessed red meat.

- Higher-quality studies looking at current evidence suggest that the effect of red meat on cancer is weak and inconsistent.

Red meat has a role in a healthy and balanced diet

Red meat has an abundance of nutritional benefits, some of which are summarised below:

1) Rich Source of Nutrients

Red meat provides valuable nutrients such as protein, iron, zinc, selenium, and certain B vitamins. The type of iron found in red meat (haem iron) is more easily absorbed in the body compared with those found in plant foods. Whilst it’s possible to get all of these nutrients from a plant-based diet, it’s more difficult and requires careful planning.

2) Complete protein

Red meat is a complete protein, so it provides all of the essential amino acids (the building blocks for protein) which the body requires for growth and repair. The majority of plant foods are not complete proteins, which means they don’t contain all of the nine essential amino acids. Vegetarians and vegans must ensure they include a mixture of different plant-based protein foods to ensure they obtain all of the essential amino acids within their diet.

3) Ideal food for a low-carb approach

Following a lower-carbohydrate approach can be very effective for weight loss and reducing our risk of certain diseases. Reducing our intake of carbs and increasing our intake of protein and fat helps to keep our blood sugar and hunger levels stable throughout the day. Eating red meat provides both protein and fat and is, therefore, an excellent food to include as part of a lower-carb approach.

Key points:

- Red meat is a great source of nutrients such as protein, iron, zinc, selenium, and certain B vitamins.

- You can include minimally processed red meat as part of a lower-carbohydrate approach.

Take home message

- Cancer is a multifactorial disease, with diet being one lifestyle factor influencing the risk of cancer.

- The research into red meat and cancer has been misrepresented in the media, creating fear and confusion amongst the general public.

- Current UK recommendations for red meat consumption are based on weak, observational evidence; an association between red meat and cancer doesn’t mean that red meat causes cancer.

- Red meat provides valuable nutrients such as protein, iron, zinc, and vitamin B12. These nutrients are more difficult to obtain from a plant-based diet.

- High-quality, minimally-processed red meat can be a part of a healthy and balanced diet.

- Many people are choosing to reduce their red meat intake for environmental and sustainability reasons; cutting down on our consumption of low-quality, heavily processed meats can be a first step for achieving a more sustainable diet.