From a nerve-racking presentation at work to running around after a busy family, we often see stress in a negative light. In extreme cases, we associate chronic stress with trauma, which can have lasting effects on our physical and mental health. However, recent science suggests that stress isn’t always bad!

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Good vs bad stress

There are two types of stress, namely distress and eustress. Distress (most commonly mentioned) makes us feel out of control and anxious, and will most likely negatively impact the immune system in the long term. It can be short or long term, but crucially, it’s perceived as something we aren’t prepared or able to cope with. Distress feels unpleasant and typically decreases our performance.

Eustress, however, is the stress that motivates and excites us. It tends to only last for short periods and is within our perceived abilities. This means we feel confident in our ability to handle the stressful situation, so it doesn’t become overwhelming. Eustress can improve our short-term performance and is similar to a fight-or-flight response before an exam or a race.

Understanding the differences between the two types of stress can help us manage stressful situations in our daily lives and improve our well-being. In a TED talk on ‘how to make stress your friend’, health psychologist Kelly McGonigal posed the question: ‘Is it merely the belief that stress is bad for us that negatively affects us?’

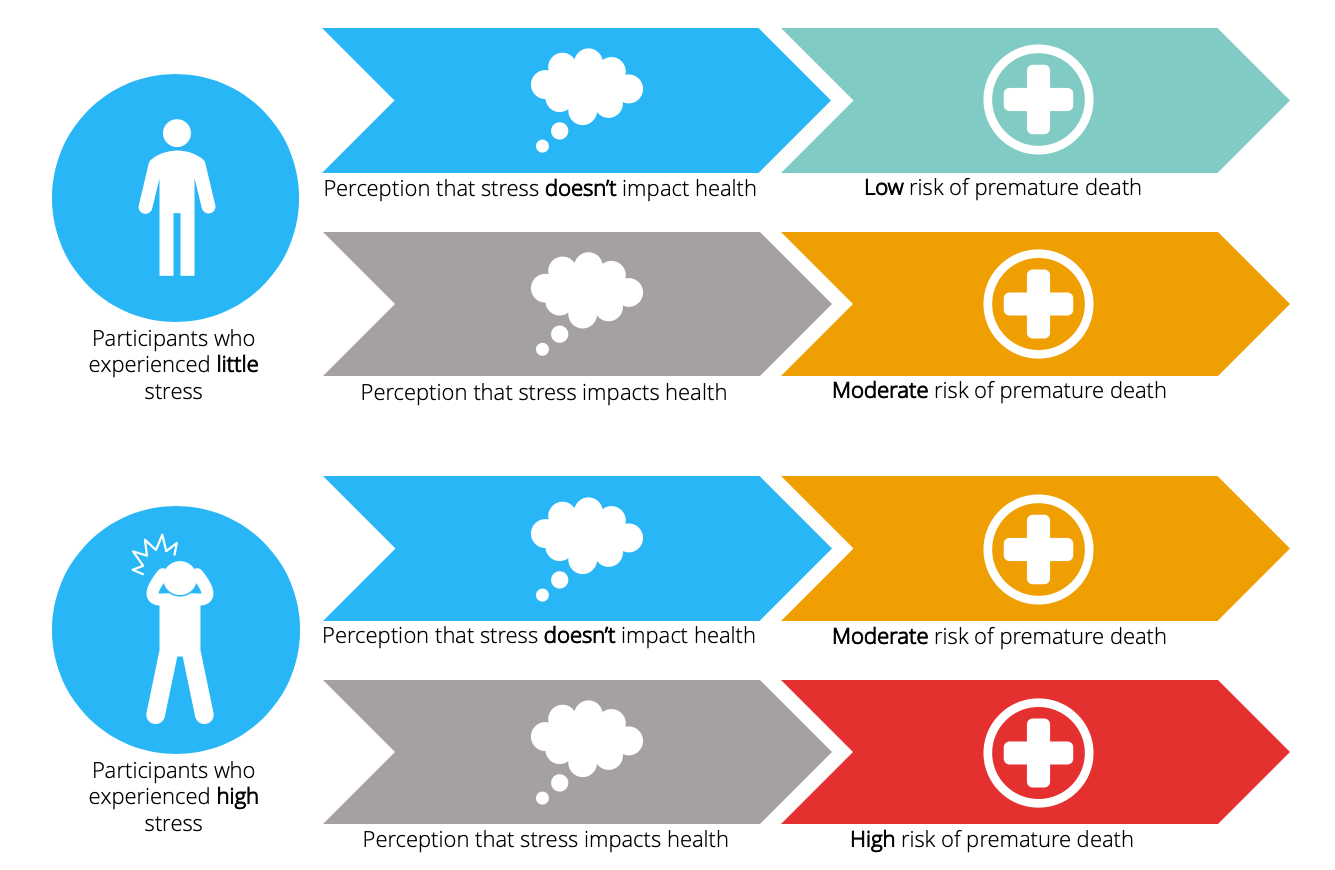

From one particular study, she noted that people who believed stress to be harmful to their health were 43% more likely to die from health-related issues, compared with those who didn’t. In fact, those who experienced higher stress levels but didn’t see it as detrimental to their health had less risk of premature death than those who had little stress in the first place.

Key points:

- Distress is the ‘bad’ stress that makes us feel out of control and might impact our health in the long term.

- Eustress is the ‘good’ stress that motivates and excites us and might improve our short-term performance in tasks.

Benefits of stress

Believing there are positive effects of stress may alter how we physically respond to it, so knowing the potential benefits of stress is helpful.

Studies have shown that manageable amounts of stress can be beneficial. Some of the positive effects of stress include improving our alertness and short-term performance and, potentially, our learning and memory abilities over more extended periods.

Animal studies have shown that stem cell growth is stimulated when rodents are exposed to moderate levels of stress over short time periods. Stem cells are important precursor cells that can develop into brain cells. After a couple of weeks, tests showed improvements in learning and memory in the rats.

Although we can’t translate animal findings to humans, this suggests that short-periods of manageable stress could be beneficial. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes a lot of sense. It was important for our ancestors to remember stressful events to avoid them in the future, ensuring their survival.

But how much stress is a manageable level?

It’s important to remember that stress can affect different people in different ways. Manageable stressors for one person may be overwhelming to another. In fact, when we’re talking about stress here, what we really mean is an individual’s response to stress, which can be described as ‘strain’.

Research suggests that people who feel resilient and confident in their ability to manage stress can handle more strain. They’re less likely to feel overwhelmed by a stressful situation. Stress physically affects these people differently, with less negative consequences.

However, even if you don’t currently feel resilient, there are ways to build this up so that stress can start to feel more manageable. This helps to improve your sense of control over stressful situations.

Key points:

- If we feel we can cope with our stressors, stress can improve our performance and alertness

- Stressful events may also result in improvements to our memory and learning ability

- Our stress response varies from person to person, based on life experiences and how resilient we currently are

What happens when we experience stress?

Stress responses are coordinated in the brain. Way back in our ancestors’ history, we needed a stress response to keep us alive, allowing us to respond to threats such as predators quickly.

Nowadays, though, it’s far more common for stress to result from non-life-threatening events, such as a busy day at work or an argument with a loved one. Despite this, our bodies still respond in the same way.

When faced with a stressful event, the brain will signal other parts of the body to take action. This response stimulates the release of hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, causing our heart rate to increase and our blood vessels to constrict. Consequently, blood pressure increases and oxygen is pumped around the body more effectively. Adrenaline also causes glucose and fats to be released from temporary storage sites around the body, creating extra energy for our fight or flight response.

However, one study found that participants who didn’t believe that stress was harmful to their health experienced an increase in heart rate, but their blood vessels didn’t constrict. These people have a lower risk of high blood pressure due to chronic stress than those with a traditional stress response.

This response mirrors what happens when we feel joy, highlighting that we can change our body’s stress response with our beliefs. An altered response may improve our well-being and mitigate some of the health impacts of chronic stress.

Key points:

- The usual stress response causes our heart to race and our blood vessels to constrict

- Stressful situations trigger the release of hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline which help us in our fight or flight response

- How we perceive stress actually impacts our body’s response, preventing a rise in our blood pressure and reducing the impact of chronic stress on our health

How can we use stress to our advantage?

So, it seems that changing the way we view stress actually impacts our physical response. If you view stress as a challenge that your body is preparing for, your body will respond differently than if you believe stress to be a threat.

Shifting our mindset can help us to access the benefits associated with eustress. As we discussed earlier, eustress can enhance our short-term performance and increase our focus on important tasks. By viewing stress as a challenge in this way, we can use it to get motivated.

Kelly McGonigal also considers evidence that suggests how we act can help to manage stress. This involves the role of the hormone oxytocin. This hormone has been nicknamed ‘the cuddle hormone’ as it’s released when we experience physical contact, like a hug.

Not many people realise that oxytocin is actually a stress hormone. It’s released during the stress response and motivates us to seek support and social contact. Oxytocin also plays a role in keeping our blood vessels relaxed and promotes heart-strengthening during times of stress. This means a human connection can increase resilience to such stress!

The study that prompted this idea tracked 1,000 people from the USA aged between 34-93 years and asked them two questions:

1) ‘How much stress have you experienced in the past year?’

2) ‘How much time have you spent helping out people in your community?’

The results suggest that stressful events increased the risk of premature death from long-term health problems such as heart disease by 30%. However, the study didn’t find this increased risk in people who spent time caring for others – highlighting that caring behaviours can also improve resilience to stress.

Mindfulness can be another stress management tool. Research suggests that mindfulness can increase our sense of control over stressful situations, reducing our strain, and resulting in a less negative stress response.

Mindfulness exercises such as mindful breathing and developing an awareness of our surroundings have been shown to reduce stress levels and negative health impacts. Importantly, mindfulness has also been shown to increase our perceived ability to cope with stress. This means we are more likely to experience eustress, rather than becoming overwhelmed.

Key points:

- Studies suggest that those who believe stress is not harmful to their health experience a physical response to stress that mirrors the biological response to joy

- Evidence suggests engaging in caring behaviours can improve resilience to stress

- Mindfulness can help to reduce stress levels and increase our perceived ability to cope with stress

Take home message

- There is ‘good’ (eustress) and ‘bad’ (distress) stress

- Different people will react differently to stress, meaning we all face different amounts of ‘strain’, even from the same situation

- How we think about stress and how we act both considerably affect how our body responds to stress

- When you feel under pressure, try to see it as good stress rather than bad stress, like a challenge that your body is rising to, rather than a threat

- Practising caring behaviours, such as calling a friend each week, and practising mindfulness can help to improve resilience to stress

- Stress might not be something to fear after all