Jump to: What is the keto diet, and how does the keto diet work? | The keto diet is effective for weight loss and type 2 diabetes | Is the keto diet sustainable? | Take home message

Nutrition

Keto diet: What is it and is it good for you?

Written by

Robbie Puddick (RNutr)

Content and SEO Lead

Medically reviewed by

Dr Rachel Hall (MBCHB)

Principal Doctor

13 min read

Last updated February 2026

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Here are four things you need to know about the keto diet:

- It’s a very low-carbohydrate (typically less than 50g of total carbohydrate), high-fat diet.

- Keto diets were initially designed to treat epilepsy in the 1920s and are now re-emerging as a mainstream treatment.

- Keto diets can be effective for weight loss and type 2 diabetes.

- Keto diets are very restrictive and may not be sustainable for many people.

The keto diet eliminates virtually all carbohydrates from your diet and prioritises a very high fat intake with moderate protein intake.

A traditional ketogenic diet would be around 80-90% calories from fat, 8-12% from protein, and 2-12% from carbohydrates.

More modern versions of the ketogenic diet have shifted to slightly increased protein and less fat while keeping carbohydrate content around 10% of calories.

It shares similarities with Atkins and low-carb diets. Still, it prioritises reaching a state of nutritional ‘ketosis’ where your liver creates ketones to fuel the brain due to low glucose availability.

The keto diet encourages the consumption of:

- Meat, particularly fatty cuts of red meat like ribeye.

- Fish, particularly oily fish like salmon.

- Dairy and heavy cream.

- Added fats like extra virgin olive oil, butter, avocado oil, and coconut oil.

- Nuts, particularly those rich in mono-unsaturated fat like walnuts.

- Green leafy vegetables like spinach and kale.

- Non-starchy vegetables like broccoli, cauliflower, and mushrooms.

The keto diet discourages the consumption of:

- Starchy carbohydrates like rice, pasta, bread, and potatoes.

- Starchy vegetables like carrots, swede, celeriac, and parsnips.

- Lentils and legumes.

- Most fruits (although some fruits, like berries, could be consumed in small quantities).

- Added sugar and refined carbohydrates.

- Ultra-processed foods.

Keto diets in epilepsy

Historians have discovered the use of fasting for treating epilepsy since 500 BC, and nutritional ketosis shares similar physiology to fasting in that glucose levels in the body fall, and it will primarily burn fat and ketones for fuel.

Modern physicians introduced ketogenic diets for epilepsy in the 1920s, and they became a widely used treatment.

However, due to the introduction of medications and the pharmaceutical industry’s influence, their use became marginalised. This is changing with more recent evidence showing the efficacy of ketogenic diets in epilepsy.

Keto diets, weight loss, and type 2 diabetes

Research has shown that ketogenic diets can effectively support weight loss and manage type 2 diabetes.

Virta Health, a company in the U.S. – led by two advocates of the ketogenic diet, Dr Stephen Phinney and Dr Jeff Volek – utilises this approach in its programmes to help manage type 2 diabetes, reduce or remove medications, and put diabetes into remission.

Virta has recently published 5-year results from their non-randomised clinical studies with promising outcomes on remission, weight loss, and medical deprescription (cessation of medication use).

More broadly, the keto diet is now the most searched term on Google for diets and weight loss, with its popularity rising globally.

While it’s effective in supporting weight loss, type 2 diabetes, and various neurological conditions such as epilepsy, ketogenic diets are restrictive, and many people may find them difficult to maintain in the long term.

Ketogenic diets typically require less than 50g of total carbohydrates per day to encourage the body into ketosis. For example, your body can be ‘booted out’ of ketosis if you have a significant portion of broccoli.

At Second Nature, we don’t exclude entire food groups or place strict rules and restrictions on what you can and can’t eat.

If you’re looking for a diet that can help with weight loss and something you can sustain in the long term, the keto diet might not be the best fit for you. Here, we have a complete guide comparing the critical differences between keto and Second Nature.

Click here if you’d like to join over 150,000 people who’ve lost weight and kept it off with Second Nature through our indulgent and healthy diet plans.

Otherwise, keep reading as we dig into the science of the ketogenic diet, its impact on weight loss and type 2 diabetes, and how sustainable an approach it is for long-term health.

1) What is the keto diet, and how does it work?

Typically, the body has two primary fuels: carbohydrates (glucose) and fats. In a ketogenic diet, you restrict your carbohydrate intake to less than 50g per day or roughly less than 10% of calories, forcing the body to primarily burn fat for fuel.

However, fat can’t be moved into the brain to be used for fuel because of something known as the blood-brain barrier, and glucose is the brain’s primary fuel source.

The liver can make new glucose from fat and protein; we call this process gluconeogenesis (pronounced glue-co-neo-gen-eesis). But it can’t produce enough to fuel the brain’s demands for glucose.

This is where ketones come in. The liver can make ketones from fats, which can cross the blood-brain barrier and be used for fuel by the brain. Other body parts, such as the heart and muscles, can also use ketones for fuel.

You’re typically considered to be in ketosis if your blood ketone level is above 1 mmol. However, some clinical trials have used a cut-off of 0.5mmol as a marker of compliance with the ketogenic diet.

Keto adaptation

As you might imagine, this flip in our physiology is quite a dramatic shift for the body.

It can take weeks or even months to entirely ‘switch on’ all the necessary pathways required to ensure the body can rely on much smaller amounts of glucose.

With such small amounts of glucose coming in through the diet in the form of carbohydrates, the glucose used in the body that remains in the bloodstream primarily comes from the liver.

Diuretic effect

This transition to nutritional ketosis has a diuretic effect on the body, and the kidneys will start to excrete more sodium, potassium, and magnesium out of the urine.

Your body also loses excess water as it burns through carbohydrate stores (glycogen) in your muscles and liver. Glycogen is stored with around three parts water for every one part of glycogen.

So, a large proportion of initial weight loss observed on a ketogenic diet will be due to water loss from depleted glycogen stores.

Potential side-effects: the so-called ‘keto-flu’

With this transition phase comes likely side effects where your body is adapting to its new physiology, sometimes referred to as the keto flu. During this time, you may experience the following:

- Headache

- Muscle cramps

- Heart palpitations

- Bad breath

- Lethargy

Many of these symptoms are likely due to added excretion of minerals out of your urine and loss of water. Staying hydrated and ensuring you’re eating enough salt, magnesium, and potassium in your meals will likely alleviate these.

Still, these symptoms typically pass within the first few days or a week or two as your body adapts.

Key points

- The body typically uses both carbohydrates and fat for fuel.

- The keto diet is a very low carbohydrate diet containing less than 50g of carbohydrates per day or 10% of calories.

- This restriction of carbohydrates forces the body to primarily use fat for fuel and make ketones in the liver to fuel the brain.

- This transition can take time to adapt to, often referred to as keto-adaptation.

- This adaptation period can take weeks or months before the body has settled.

- You may experience symptoms during this time, but they can be alleviated by drinking enough water and eating enough salt.

2) The keto diet can help with weight loss and type 2 diabetes

The early use of the ketogenic diet was primarily for children living with epilepsy, as clinical trials showed significant improvements in the number of seizures experienced.

However, more recent attention has been placed on its use to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Obesity and weight loss

A clinical trial involving 17 men living with obesity compared the effect of a ketogenic diet to a moderate carbohydrate diet on weight loss, hunger, and food satisfaction.

The trial was known as a cross-over study, where all participants completed four weeks on each diet, with a ‘washout’ period in the middle where they’d eat a regular diet.

The study was known as an ‘ab-libitum’ study, where the participants were provided with all their meals and instructed to eat as much as they wanted. The idea was to eat until they were comfortably full and not beyond this point.

After four weeks, the ketogenic diet saw more weight loss than the moderate carb group (-6.34kg vs -4.53kg).

Interestingly, self-reported hunger was also significantly lower in the ketogenic diet. Food/meal satisfaction wasn’t different between the two groups.

Plasma ketone levels averaged 1.52mmol in the keto group, confirming adherence to the diet.

However, the limitations of this study were the relatively smaller sample size and the control over adherence as the meals were provided.

The potential drawback of the keto diet is whether people can adhere to it in the long term in free-living conditions.

Interestingly, a larger randomised controlled trial in 120 overweight participants showed similar findings. The study compared a low-fat diet (<30% calories from fat) to a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (less than 20g of carbohydrates per day) on weight loss.

The critical difference in this study was that the meals weren’t provided, and the participants were free-living in their community. They were provided menus, recipes, group support, and diet instruction.

After six months, the ketogenic diet was nearly twice as effective at supporting weight loss than the low-fat diet (-12.9% vs -6.7%). Interestingly, adherence to the keto diet was higher than the low-fat group (76% vs 57%).

Contrastingly, a randomised controlled trial in 307 participants found no difference in weight loss between ketogenic and low-fat diets after two years. Both groups lost 11% of their body weight after 12 months and 7% after two years, with a 4% regain.

Both groups in this study were supported through behaviour change sessions throughout the trial.

This study suggests that combining dietary advice with a lifestyle intervention that includes psychological support can effectively support weight loss, no matter the general makeup of the diet.

Type 2 diabetes

Recent evidence suggests that diets lower in carbohydrates and higher in fat and protein can support improvements in type 2 diabetes.

Lower blood sugar levels, improved insulin sensitivity, cessation or reduction in medications, or full remission are often observed in individuals living with type 2 diabetes after adhering to lower-carbohydrate diets.

A small pilot study placed ten participants living with obesity and type 2 diabetes on a strict low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet for two weeks.

This was an inpatient study where the meals were provided, and they were instructed to eat ab-libitum.

The keto diet saw a spontaneous reduction in energy intake by over 1,000 calories per day, plasma blood sugar levels normalised and insulin sensitivity improved by 75%. Additionally, as measured by HbA1c, average blood sugar levels dropped by 0.5%.

This is a very small study without a control group for comparison. However, more extensive trials have since shown similar results.

A large non-randomised clinical trial in 363 people living with obesity (102 had type 2 diabetes) instructed their participants to self-select either a ketogenic diet or a standard higher carbohydrate diet restricted to 2200 calories per day. 143 chose the low-calorie diet, and 220 chose the ketogenic diet.

The results showed that the individuals on the ketogenic diet were able to eat fewer calories – despite being instructed to eat ab-libitum – than the low-calorie diet.

Participants with type 2 diabetes lost more weight on the ketogenic diet compared to the low-calorie diet (-12kg VS -7kg), and HbA1c (a measurement of average blood sugar levels) dropped by 19.35% in the ketogenic diet group compared to 6.45% in the low-calorie group.

The results from these studies are supported by other trials showing that a ketogenic diet tends to support more significant weight loss and blood sugar improvements compared to standard low-fat diets higher in carbohydrates.

This effect is primarily attributed to hunger and fullness signals, which improve on the ketogenic diet, which we call satiety.

This increased satiety supports individuals in eating fewer calories, losing more weight, and reducing their blood sugar levels.

Do you need to cut carbs completely?

The short answer is no. Whilst the ketogenic diet promotes positive improvements in weight and blood sugar levels; it’s not to say that this is the only way to achieve these goals.

A randomised controlled trial in 307 participants (mentioned above) showed similar levels of weight loss between a keto diet and a lower-fat diet after two years. Both diets were accompanied by extensive behaviour change support.

Similarly, a recent randomised controlled trial investigated the impact of a ketogenic diet (less than 12% calories from carbohydrates) and a Mediterranean diet (around 37% calories from carbohydrates) on weight loss and blood sugar levels in individuals living with pre-diabetes or type 2 diabetes.

After 12 weeks, the ketogenic diet lost more weight than the Mediterranean diet (-6.9kg vs -5kg), but after 36 weeks of follow-up, both diets achieved a similar weight loss of around 6kg.

Blood sugar level improvements were also similar between the groups. The ketogenic diet saw HbA1c levels reduced by 9% and the Mediterranean diet by 7%.

The reason for the similar improvements between the two groups is likely the focus on diet quality in this trial. Both groups were instructed to avoid added sugars and refined carbohydrates.

This meant that while the groups had different carbohydrate levels, they consumed similar-quality diets. They would have been consuming primarily whole foods with a limited amount of ultra-processed foods.

This mirrors Second Nature’s approach to nutrition. While we recommend a more sustainable balance of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins – we focus primarily on whole-food consumption and reducing your intake of ultra-processed foods.

You can then personalise your balance of macronutrients (carbs, fats, proteins) to suit your preferences, cultural values, and lifestyle.

Key points

- The ketogenic diet supports significant weight loss.

- It seems to do so by promoting improved satiety and allowing individuals to consume fewer calories.

- The ketogenic diet also supports improvements in blood sugar.

- However, more recent trials have shown that if diet quality is prioritised, you can achieve similar results to a ketogenic diet over the long term with more carbohydrates.

- Prioritising whole food consumption will help you achieve significant health improvements. You can then personalise your carbohydrate intake to suit your preferences.

3) Is the keto diet sustainable in the long term?

In clinical trials, adherence to the ketogenic diet is good in the short term, but like most diets, it wanes after six months or so, and most trials show some level of weight regain on average.

Diets with strict rules on what you can and can’t eat are typically difficult to maintain in the long term. Some people seem to thrive under strict conditions, but for most, a little flexibility is needed to support adherence to a healthy diet.

The ketogenic diet is unique because we have a marker in the blood to determine whether individuals are following the diet. By measuring blood ketone levels, we can measure adherence.

In a randomised controlled trial comparing a ketogenic diet to a low-fat diet on weight loss, the ketogenic diet group were instructed to eat no more than 20g of carbohydrates per day (roughly the equivalent of one slice of bread, or four teaspoons of sugar) for the first three months.

They were then allowed to increase their carbohydrate intake by around 5g per day until a sustainable level was reached.

The study showed that 63% of individuals had urine ketone levels indicating they were in nutritional ketosis after three months. After six months, this number dropped to 28%.

Showing that a third of individuals weren’t adhering to a ketogenic diet after three months and over two-thirds at six months.

Similarly, a randomised controlled trial comparing a ketogenic diet to a Mediterranean diet on weight loss and blood sugar control. They also analysed adherence and preference to the diets on follow-up.

The study showed that blood ketone levels peaked at 1.1mmol (indicating nutritional ketosis) during the study phase when their meals were provided for them (weeks 1-4).

However, during the free-living phase of the study, blood ketone levels dropped to 0.51mmol.

This drop in ketones is because their carbohydrate intake increased from 12% of calories to 18% after the meals were no longer provided. Carbohydrate intake then increased to around 33%, on average, after 36 weeks.

The study also showed that individuals preferred the Mediterranean diet during the free-living phase and found it easier to follow.

Strict diets are hard to follow. Whether you’re following a ketogenic diet or a low-fat vegan diet. Any end of the extreme is always going to make it more challenging to maintain in the long term.

The white bear effect

There’s a theory in psychology called the white bear effect. It’s based on research that’s shown that when people try and avoid thinking about something specific, the thoughts of this thing become more accessible in their minds.

We can translate this across to food as well. Suppose you start a ketogenic diet, lose weight, drop blood sugar levels, and feel good. But after a while, the message that you can’t eat carbohydrates and must avoid them becomes louder in your mind.

The more you try to avoid this thought, the more accessible it becomes. Over time, the cravings for carbohydrates will likely increase, and you might struggle to adhere to the diet.

Key points

- Blood ketone levels can be used to measure adherence to the ketogenic diet in clinical trials.

- Studies have shown that whilst adherence is good in the short term, people tend to increase carbohydrate intake and can’t adhere to the diet in the long term.

- Strict diets may be too challenging for many people, and more flexible diets that don’t exclude entire food groups will be easier to follow.

Take home message

Some people will thrive on a ketogenic diet and feel it’s something they can maintain for the long term.

However, for most people, restricting carbohydrates to a point where they can reach and maintain nutritional ketosis in the long term is too challenging.

It’s likely that despite the positive effects of the ketogenic diet on our health, the inability of most people to follow the diet in real-world conditions means more flexible approaches are needed.

Click here if you’d like to try Second Nature’s 7-day balanced meal plan, trusted by the NHS.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

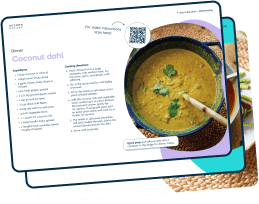

Download our free, indulgent 7-day meal plan

It includes expert advice from our team of registered dietitians to make losing weight feel easier. Subscribe to our newsletter to get access today.

You might also like

As seen on

As seen on