How hunger works

Hunger is regulated by a complex web of communication pathways between the gut (the GI tract) and the central nervous system (CNS).

These two systems interact through several hormones, such as ghrelin, released from the stomach to signal hunger and those secreted from the GI tract, like GLP-1, PYY, and CCK.

You can think of ghrelin as your hunger hormone. When ghrelin is high, this will increase the feeling of hunger and drive you to eat.

GLP-1, PYY, and CCK are our fullness (satiety) hormones. When they’re high, hunger will be low, we’ll feel full or satiated, and our desire to eat will be lower.

There’s also a different type of hunger known as hedonic hunger when you’ll feel a higher desire to eat despite not feeling hungry or having any physical requirements for your food cravings.

What influences hunger?

As hunger is regulated by systems connecting the body and brain, many factors can increase your physical and hedonic hunger. For many people, however, there seem to be a few key influences.

High consumption of ultra-processed foods has been shown to override the physical fullness cues (satiety signals) that we typically get from eating meals based on whole foods.

For example, if you eat a steak, jacket potato, and salad with an olive oil dressing, you’ll likely feel full and satiated afterwards.

The combination of fat, fibre, protein, essential micronutrients and polyphenols, and starch in this meal would increase the satiety hormones GLP-1, CCK, and PYY and decrease the hunger hormone ghrelin to stop you from overeating.

Compare this to a meal from a fast-food restaurant of a cheeseburger, fries, and a soft drink.

While rich in energy from refined carbohydrates, sugar, and fat, it’s much lower in fibre, protein, and essential nutrients that support the release of the satiety hormones from the gut.

So, despite consuming a high amount of energy in the meal, the brain doesn’t receive the same amount of signals from the gut to let it know you’ve eaten enough – so your hunger is likely to remain higher.

This also seems true when we eat carbohydrates in isolation, such as crisps or a slice of toast.

Carbohydrates have been shown to result in higher levels of ghrelin in the hours after consumption compared to fat and protein which keep ghrelin levels lower for longer.

Hunger can also be increased when you don’t eat enough food and try to restrict yourself on a diet. You’re simply not giving your body the right signals to promote the feeling of fullness, so your brain will continue to tell you to eat.

It’s also possible you’re not enjoying the foods you’re eating because you’re too focused on eating bland, so-called ‘healthy’ low-calorie foods. Research has shown that if we can get more satisfaction with healthy foods, we can control our intake.

Sleep also influences the relationship between the GI tract and the CNS. Studies have shown that individuals who are sleep deprived have higher levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin and are much more likely to overeat calories than those who sleep more than 7 hours a night.

Alongside this, our current food environment is awash with temptations of ultra-processed foods and sweets that play into our food reward system.

The anticipation of foods rich in starch, sugar, and refined fats spikes dopamine levels in the brain – and you’re more likely to eat these foods to experience the reward you’re anticipating.

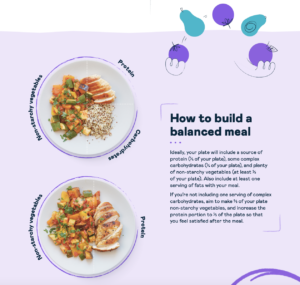

At Second Nature, our nutritional guidelines are designed to lower hunger and increase feelings of fullness. They’re rich in protein, fibre, fat, and complex carbohydrates to send the right signals to the brain so you can control your eating habits.

You’re also supported by a registered dietitian or nutritionist who’s online to support you five days a week.

If you’re sick of feeling hungry all the time and want to make weight loss feel easier, click here to join over 150,000 others who’ve achieved lasting weight loss and reduced hunger with Second Nature.

Otherwise, keep reading as we dig into the science behind hunger, why you always feel hungry, and what you can do about it.

1) Your diet is too high in ultra-processed foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugar

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) can be loosely defined as commercially manufactured foods that no longer resemble the ingredients used to make them. A typical example would be cornflakes.

Corn would have been farmed, broken down, chemically and mechanically changed to resemble the golden flakes presented to you in a convenient box.

UPFs typically contain more than five ingredients and many chemical stabilisers, emulsifiers, and preservatives.

Compare this to whole grains like quinoa or brown rice. They’re harvested, placed in packaging, and then we cook them in their whole form.

Whilst cheap and convenient, these foods seem to significantly impact our hunger and fullness signals and promote the increased desire to eat more.

Observational studies show that individuals who consume the highest amount of UPFs are 79% more likely to be obese than individuals with the lowest intake.

The ability of UPFs to increase hunger and overeating was demonstrated in a randomised controlled trial with 20 weight-stable individuals.

The participants were randomised to either a diet rich in UPFs or a whole-food diet. All meals were provided, and participants were instructed to eat as much as they liked.

The results showed that individuals eating the UPF diet consumed 459 calories per day more than those consuming the whole diet. Unsurprisingly, this led to weight gain in the UPF group, while the whole food group lost weight.

Despite eating more, the UPF group had higher circulating levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin and lower levels of satiety hormones PYY and GLP-1.

So, UPFs are associated with obesity, and clinical trials have demonstrated they lead to increased hunger, resulting in higher calorie intake and weight gain.

Blood sugar levels

An element of hunger and appetite control are your blood sugar levels. The brain constantly receives feedback about glucose levels in the bloodstream as a marker of energy available for the body’s cells.

When these levels drop too low, which we call hypoglycemia, this is picked up by the brain, and it responds by increasing hunger levels that encourage you to eat. You’re also likely to feel light-headed, lethargic, and jittery.

This was demonstrated in clinical data from the ongoing study on nutrition from Zoe, known as the PREDICT trial investigating individual responses to food and its relationship to health outcomes.

The study analysed data from 763 participants and found that individuals who experienced glucose dips (hypoglycemia) after meals had increased hunger and consumed 312 calories more per day on average compared to those who didn’t experience glucose dips.

This variation in blood sugar control was even seen between participants consuming the same meals, suggesting that some people are more sensitive to consuming certain carbohydrates and sugar than others.

Balance your intake

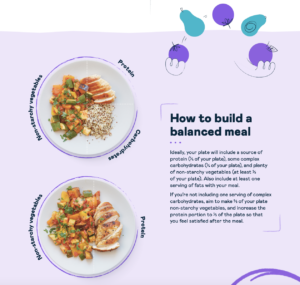

A way to control your hunger, balance your hormones, and control your intake is to enjoy a lower-carb diet based on whole foods. This approach ensures stable energy release, increases feelings of fullness and can help you lose weight.

A healthy eating pattern is rich in protein like oily fish, meat, or tofu, whole grains like quinoa, legumes, plenty of fruits and vegetables, and healthy fats like olive oil and nuts.

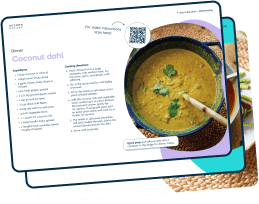

If you’d like to try a 7-day meal plan and experience what it feels like to eat delicious, nutritious foods that leave you satisfied and stabilise your blood sugar levels, click here.

Key points:

- Ultra-processed foods are broadly defined as those that no longer resemble the ingredients used to make them.

- A higher consumption of ultra-processed foods has been shown to lead to increased hunger and weight gain.

- Blood sugar control can also affect your hunger, and studies have shown that individuals who are sensitive to carbohydrate intake and experience low blood sugar are more likely to feel hungry and overeat.

2) You’re not eating enough

The brain is constantly receiving signals from the body letting it know how much energy is stored in our fat cells, and how much energy we’re consuming in each meal.

As we’ve discussed, ghrelin and the gut-derived hormones PYY, CCK, and GLP-1 have a big role in this communication.

Another key hormone is one known as leptin. Leptin is released by your body’s fat cells, which informs the brain how much fat we have stored in our body’s adipose tissue (the fat beneath the skin).

When we restrict our calories too severely, leptin levels in the body fall, and this starts a cascade of events known as metabolic adaptation; another technical term for this is adaptive thermogenesis.

Your metabolism will fall, your hunger levels will increase, and your body will attempt to preserve your existing fat stores as much as possible while encouraging you to start eating more.

This is our body’s way of protecting us and ensuring our survival during times of famine.

Much of our understanding of this phenomenon is based on the Minnesota starvation experiment. A group of men were restricted to around 1500 calories per day for six months whilst walking at least 22 miles a week.

Unsurprisingly, the participant’s metabolism fell sharply, they lost weight and continued to experience extreme hunger and discomfort throughout the experiment.

Worryingly, the participants reported higher levels of emotional distress, depression, and a psychological condition known as hypochondriasis, where you feel overly concerned that you have a severe illness or disease.

More recent clinical trials have replicated these findings alongside measurements in key hormones regulating hunger.

A study on 32 participants found that ghrelin (the hunger hormone) levels increased by 18% after three weeks of caloric restriction and leptin levels also dropped by 44%.

What you’re eating matters

While you’re likely to experience some hunger during a weight loss journey, recent research has suggested that altering the balance of your diet can lower hunger levels.

A clinical trial compared two high protein diets, one low-carb and the other moderate-carb, on weight loss, hunger, and appetite. The participants were provided with their meals and asked to eat as much as they liked.

The study showed that the low-carb group consumed fewer calories than the moderate-carb group and lost more weight (-6.34kg vs -4.53kg).

Interestingly, the low-carb group had lower levels of self-reported hunger and a lower desire to eat despite being able to eat fewer calories.

This suggests that enjoying a higher protein diet that doesn’t restrict fat, may help you lower your calorie intake without feeling too hungry.

This may be explained by the influence of fat and carbohydrates on reward signalling in the brain.

A recent study showed that restricting dietary fat to less than 30% of total energy during weight loss changed dopamine signalling in the brain. This encouraged the consumption of ultra-processed foods rich in refined carbohydrates, added fat, and sugar.

Large randomised controlled trials have also suggested that people struggle to restrict fat during weight loss. This can lead to poor diet adherence and encourage overconsumption and weight cycling.

Key points:

- When you try to cut your calories too much, your body responds by slowing your metabolism, increasing hunger, and encouraging you to eat more.

- However, clinical trials comparing low-carb to moderate and higher-carb diets have suggested that if you don’t restrict fat and eat enough protein, you can reduce hunger and eat fewer calories.

- Interestingly, more energy-dense foods rich in healthy fats may support weight loss by reducing hunger.

3) You’re not sleeping well

If you’ve had a night of poor sleep, you might feel constant hunger and be more inclined to reach for energy-dense foods.

A clinical trial showed that when people had at least 8.5 hours of sleep, the part of their brain that controls feeding and appetite had a very low activation level.

They were less hungry, had a lower energy intake, and had lower activation of their reward and addiction systems in their brain.

When the scientists reduced the participant’s sleep to 4.5 hours, they reported increased hunger and appetite. They were also more likely to feel hunger pangs and choose snacks with 50% more calories than those with 8.5 hours of sleep.

Additionally, the sleep-deprived people struggled to resist what the researchers called ‘highly palatable, rewarding snacks’ (meaning cookies, ice cream, and crisps) even though they had consumed a meal that supplied 90% of their daily caloric needs two hours before.

A lack of sleep also means we’re less likely to exercise the next day. Research has shown that long-term exercise and higher fitness levels help the brain manage intake by changing how it responds to food cues, which may help reduce hedonic hunger.

Sleep deprivation also increases our cortisol levels, increasing appetite and impacting our food choices.

Five ways to improve your sleep:

- Have a regular bedtime routine and get up at the same time each day.

- Avoid technology 30-60 minutes before bedtime.

- Try calming activities before bedtime, like reading.

- Avoid caffeine after midday.

- Get regular daylight exposure.

Key points:

- Getting enough sleep helps regulate intake by having lower activity levels in the brain’s reward centres.

- In contrast, not sleeping enough increases the activity in these reward centres, increases hunger and leads to higher calorie intake.

- Sleep can also impact our exercise levels, which has been shown to positively affect the brain’s reward centres in response to food.

Take home message

In truth, there are hundreds of reasons why you might be feeling hungry. Medical conditions (like hyperthyroidism) and genetic influences may also play a role, such as how your brain responds to leptin.

However, in our experience at Second Nature, many people find themselves eating a poor diet, restricting themselves too much, and not prioritising their sleep.

By focusing on these three areas, you’re likely to experience a reduction in your hunger levels, which can help you manage your intake, lose weight, and live more freely without feeling preoccupied with food.

If you’d like to try a 7-day meal plan and experience what it feels like to eat delicious, nutritious foods that leave you satisfied and stabilise your blood sugar levels, click here.