Here’s why sugar isn’t good for you:

- It increases your risk of type 2 diabetes.

- Reduces your energy levels.

- Increases your risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Increases your risk of heart disease.

- Increases craving for sweet and ultra-processed foods.

- Effects acne and skin health.

- Is bad for your teeth.

While we don’t need to eat a no-sugar diet to be healthy, we all know sugar isn’t good for us. Exactly how it negatively impacts our health is slightly more intriguing.

Understanding how sugar affects our bodies is essential to encourage us to reduce sugar intake. Here are some practical tips on how to stick to a lower-sugar diet.

Before we explore the adverse health effects of sugar, let’s discuss what it is.

Sugar is the simplest form of carbohydrate. Glucose (e.g. from broken-down starches like bread and pasta), fructose (fruit), and sucrose (table sugar, a combination of glucose and fructose) are all different types of sugar.

All sugar results in similar adverse effects when over-consumed. However, there are differences in how our bodies process sugars.

Glucose metabolism occurs within all cells throughout the body, whereas fructose is metabolised in the liver.

The evidence is mixed, but some research suggests that fructose has worse effects on our health in the long term than glucose.

The idea is that fructose metabolism promotes visceral fat (fat around your organs), which has been linked to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

However, there’s not enough robust evidence to suggest that fructose specifically is worse for you than other sugars.

Some evidence suggests the effects of fructose are down to overeating overall, not fructose per se. Many foods sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup, such as soft drinks, are easy to over-consume.

Trying to decide which type of sugar to avoid is a case of finding the lesser of two evils. At the end of the day, sugar is sugar. Now, on to how it can negatively impact our health.

Medication-assisted weight loss with a future focus

Start with Wegovy or Mounjaro, transition to habit-based health with our support

Increases the risk of type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is characterised by high blood sugar. There are many potential answers to the question of what causes diabetes.

The uncertainty stems from whether weight gain results in insulin resistance (where our body does not respond to insulin) or vice versa.

The answer to this question determines how you treat individuals with type 2 diabetes or ‘pre-diabetes’ (impaired glucose regulation).

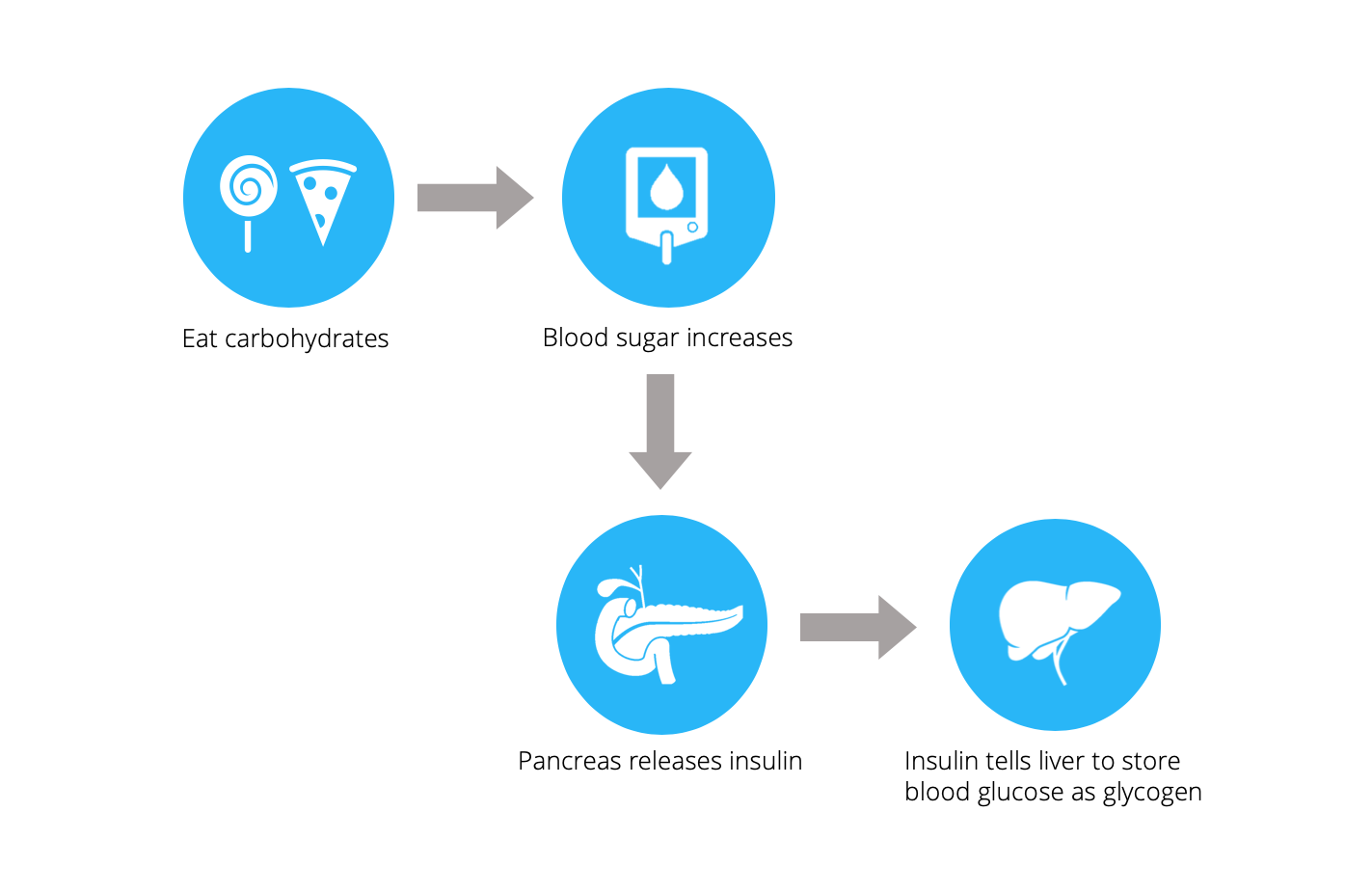

A quick note on how our bodies process sugar:

Although theories differ on what comes first between insulin resistance and weight gain, excessive refined carbohydrate consumption seems to be implicated in most theories.

Here is a detailed review of the most interesting theories. We can briefly summarise them to see how sugar plays a part in all these theories:

-

- Professor Taylor, a professor of medicine and metabolism at the University of Newcastle, suggests that the first step of diabetes is overeating food, mainly carbs. This leads to some weight gain, or slight insulin resistance, which develops into a self-perpetuating cycle. Sugars promote fat accumulation around the liver, as excess carbohydrate is converted into fat to be stored in the liver. By this theory, sugar increases weight gain and insulin resistance, leading to type 2 diabetes.

- Another theory of how diabetes develops is supported by Dr Peter Attia – a surgeon from the US who developed pre-diabetes many years ago and successfully reversed the condition. This theory draws upon the facts that: a) refined grains and starches elevate blood sugar in the short term, and b) some evidence suggests that sugar directly leads to type 2 diabetes. According to Dr Attia, sugar causes diabetes via insulin resistance rather than weight gain. This could explain how lean people can still develop type 2 diabetes.

- A slightly different angle on the matter is presented by Professor Rodger Unger, who suggests glucagon action is crucial to developing type 2 diabetes. Glucagon tells the liver to release stored glucose into the blood. In a healthy person, overeating leads to spikes in insulin and suppressed glucagon. This process results in normal blood glucose levels. Type 2 diabetics do not have the same response and, as a result, have chronically elevated blood sugar. Professor Unger proposes that high levels of insulin in the blood from overeating (i.e. weight gain) is the first step to type 2 diabetes. By this theory, sugar raises blood sugar in the short-term, increasing insulin secretion, and directly leading to diabetes.

- Dr Malcom Kendrick highlights two examples of people who don’t fit the model that more body fat means a higher risk of diabetes. Sumo wrestlers (incredibly fat) exhibit few cases of diabetes, whereas 100% of people with Beradinelli-Siep lipodystrophy (they have almost no fat cells) have diabetes. Dr Kendrick proposes that if there is somewhere for the excess energy to go, insulin and blood sugar levels will not rocket. For sumo wrestlers, excess energy is burnt up from intensive training, whereas people with Beradinelli-Siep lipodystrophy have no fat cells to store excess energy, despite high insulin levels. This leads to insulin resistance. According to Dr Kendrick, eating too much sugar forces our bodies to produce lots of insulin and store fat (weight gain), and then insulin resistance develops to block further weight gain. Yet again – sugar is at the core of the problem.

As each of these theories suggests, excess carb consumption seems to be one fundamental factor in developing type 2 diabetes.

This is seemingly easy to address by reducing dietary intake of sugar and highly processed carbohydrates.

Key points:

- There are many different theories of what causes type 2 diabetes.

- A common theme in all the theories is dietary sugar.

- Restricting our intake of highly-processed carbohydrates is the best way to address this.

Reduces energy levels

Ever felt an overpowering need to be horizontal after eating a large pizza? We have all been there.

As we have discussed, eating refined carbs causes a dramatic spike in blood sugar and a resulting rush of insulin to counter the spike. Following this, blood glucose levels drop, and our energy levels crash.

Research suggests that the neurotransmitter (a chemical messenger) orexin plays a role.

A lack of orexin leads to narcolepsy (a brain disorder that causes people to fall asleep suddenly) in humans and animals. This suggests it’s heavily involved in keeping us feeling awake.

Glucose inhibits the action of orexin. This doesn’t mean we pass out whenever we eat carbs/ sugar, as some orexin cells measure energy changes whilst others maintain arousal.

But it could explain why we feel sluggish after digesting refined carbs. Interestingly, proteins have the opposite effect and stimulate the action of orexin.

In addition, when we feel tired, we tend to want carbs/ sugar more. So overeating sugar could lead to a positively reinforcing cycle of eating carbs, feeling tired and craving more carbs.

Key points:

- Eating refined carbs causes dramatic fluctuations in blood sugar and hence energy crashes.

- The neurotransmitter orexin, which is inhibited by glucose, may play a role.

- Feeling tired increases our desire for sugar, promoting a vicious cycle.

Increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia here in the U.K. It is characterized by an ongoing decline of cognitive function that affects memory, thinking skills and other mental abilities.

Recently, Alzheimer’s has been referred to as ‘type 3 diabetes’ or a brain form of diabetes. This is because the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s exhibits similarities to that of diabetes, which could mean that sugar plays a role in its development.

There is a staggering link between Alzheimer’s and type 2 diabetes. Those with type 2 diabetes are at least twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s compared with healthy people. This by no means implies causation but demonstrates considerable overlap between the two conditions.

Dr Suzanne De La Monte, who pioneered the idea of Alzheimer’s disease being ‘type 3 diabetes’, wrote a comprehensive review on the topic.

Dr De La Monte highlighted that the brain needs insulin for many reasons, including taking up glucose for energy, producing neurotransmitters and stimulating functions required to make new memories.

In Alzheimer’s, the brain is not very sensitive to insulin, so it struggles to take up sugar from the blood, resulting in brain cells starving to death.

So it seems the brain becomes insulin resistant in Alzheimer’s. Here we can see a common theme with type 2 diabetes.

If Alzheimer’s is ‘type 3 diabetes,’ then a diet aimed at managing diabetes should equally prevent or slow the progression of Alzheimer’s. Namely a low-sugar/ lower-carb diet.

Key points:

- Alzheimer’s disease is sometimes referred to as ‘type 3 diabetes’.

- Individuals with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to get Alzheimer’s disease.

- In Alzheimer’s, the brain becomes insulin resistant, leading to brain cell death.

- A low-sugar diet could slow the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Increases the risk of heart disease

Fat has recently been vilified in the media as the unequivocal cause of heart disease. Public health dietary recommendations for the prevention of heart disease suggest:

“All individuals should be strongly encouraged to reduce total and saturated fat intake.”

These recommendations are built upon observational evidence that noted an association between saturated fat and heart disease. However, these studies do not establish causation but point towards a trend.

Additionally, many of these studies base their conclusions on markers of heart disease, such as signs of inflammation in the body, rather than hard endpoints, such as heart disease mortality.

There is equal observational evidence suggesting that sugar, rather than fat, is strongly associated with the hard endpoint of death from heart disease.

On top of this, type 2 diabetes is a significant risk factor for heart disease, which suggests sugar plays a part.

There are many theories as to how sugar might increase heart disease risk, including:

- Sugar overloads liver → more significant accumulation of fat → fatty liver disease → increased risk of diabetes → increased risk of heart disease

- Sugar consumption → raised blood pressure

- Sugar consumption → increased chronic inflammation

- Sugar consumption → body turns off appetite control system → weight gain

Dr Malcom Kendrick proposes a different way that sugar increases heart disease risk. In his 62-part blog series, he thoroughly examines what causes heart disease.

In the piece focusing on diabetes, he notes a gap in the explanation for the increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in diabetes.

In diabetes, conventional risk factors for heart disease, such as blood pressure, are raised, yet most other ‘traditional’ risk factors are unchanged.

So this begs the question: what causes the increased risk of CVD with type 2 diabetes? How does high blood sugar cause its damage?

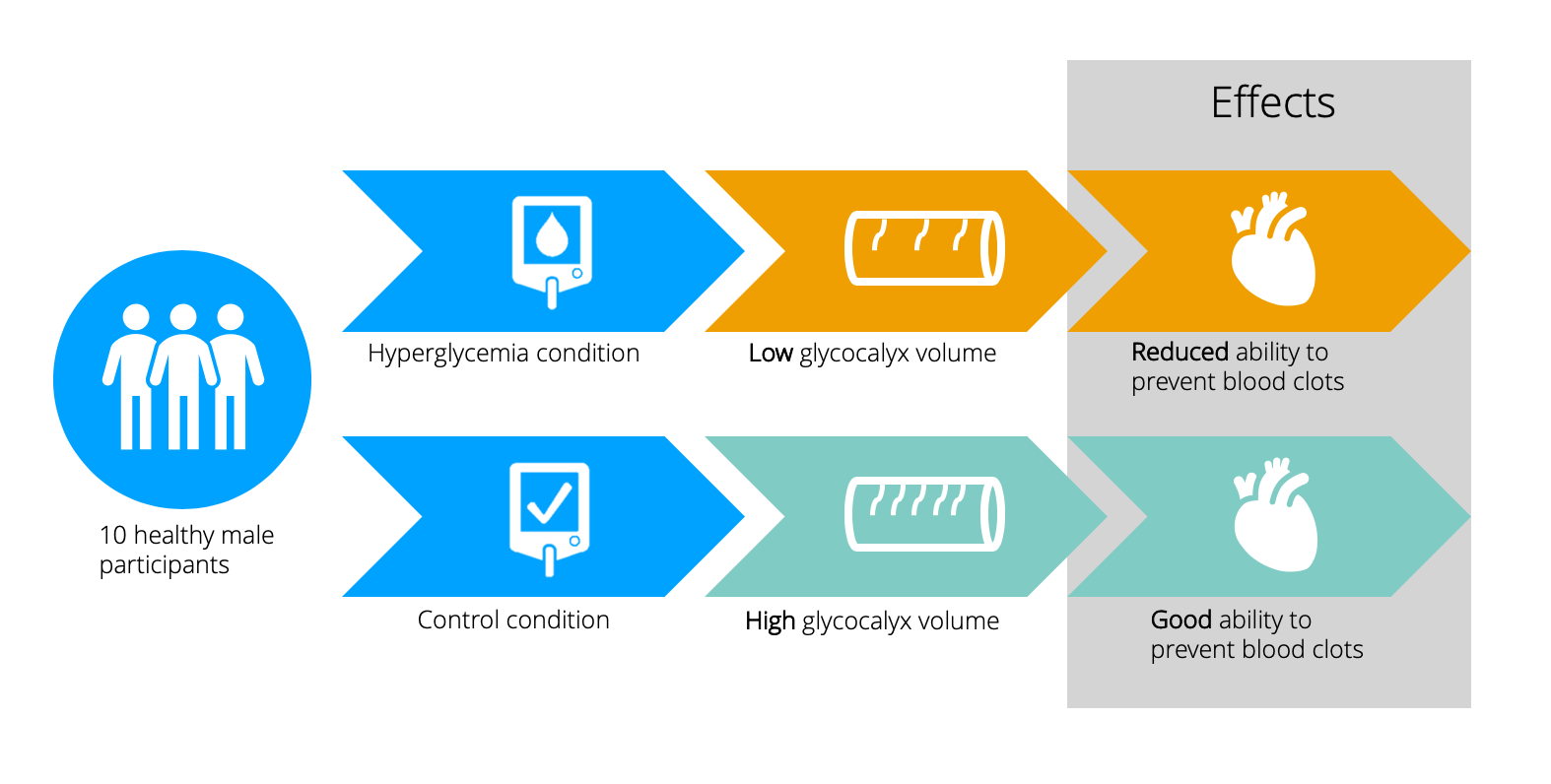

Answering these questions, Dr Kendrick introduces the glycocalyx (pronounced gli-co-kay-licks). This is a slippery, slimy layer inside our blood vessels, lining our endothelial cells that, under a powerful microscope, looks like a billion tiny hairs.

The ‘hairs’ are long strands of proteins and sugars bound together. Their function – many! But mainly to protect the underlying endothelium from damage and prevent blood clotting.

Research published by the American Diabetes Association suggests that high blood sugar significantly reduces glycocalyx volume and results in endothelial damage, as well as reduces its ability to prevent blood clotting.

In this way, diabetes (or high blood sugar) increases the risk of heart disease by damaging the glycocalyx, leading to damaged endothelium and an increase in blood clot risk.

Sugar significantly spikes our blood glucose levels in the short term. By Dr Kenrick’s theory, too much sugar directly leads to heart disease by damaging the glycocalyx.

Key points:

- Sugar has been associated with heart disease.

- Type 2 diabetes is a significant risk factor for heart disease.

- Dr Malcom Kendrick suggests sugar directly increases the risk for heart disease by harming the layer inside our blood vessels called the glycocalyx.

Increases cravings

If it’s difficult to resist cravings for sweet foods when they arise. Even when we know we should avoid that 4 p.m. chocolate bar – the desire is sometimes overwhelming. The paradox is that eating sugar makes you crave more sugar!

A potential reason for this is that tasting something sweet activates pleasure-generating brain circuitry.

Animal studies demonstrate that rats fed sugar for intermittent periods show signs of addiction and dependence on the sweet stuff.

However, this study restricted access to sugar to small windows, which could explain why rats appeared dependent. Studies that give access to sugar around the clock show fewer addictive behaviours in animals. In addition, you get the same effect with rats if you use an artificial sweetener instead of sugar.

This suggests that sugar cravings are about the taste rather than the sugar itself.

Supporting this idea, research in humans indicates that increased tasting of sweet flavour increases preference for sweet foods and subjective pleasure gained from those foods.

For this reason, artificially sweetened foods are not a great alternative to sweet treats as they still increase our preference for sweet tastes.

So eating more sugar makes us develop a preference for sweet foods and leads us to crave these foods more, which is another reason to cut down on sugar.

Key points:

- Animal studies show that rats fed sugar show signs of dependence.

- Human studies suggest that increasing the amount we taste sweet food increases our preference for sweet foods.

- Artificial sweeteners still taste sweet so are not the best alternative!

Effects acne

Acne is a common frustrating skin condition. Research has explored links between acne and diet.

In the past, dairy was under fire. The proposed mechanism is that dairy increases the hormone IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor). IGF-1 may contribute to sebum production and inflammation, which is implicated in acne.

Interestingly, skimmed milk was highlighted as more of an issue for acne than whole milk.

The suggestion is that the processing skimmed milk undergoes increases the availability of the factors implicated with acne and milk, plus skimmed milk has less oestrogen (a hormone thought to reduce acne).

However, all the evidence implicating dairy with acne is weak. Most of the evidence is based on self-reports of food intake and acne severity, which are unreliable.

Additionally, most studies are observational, so causation cannot be inferred.

Emerging data suggests that a link between blood sugar levels and acne is much more likely.

An intervention trial published by the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition demonstrated that a low glycaemic index (GI) diet improved acne in young males.

The potential explanation is that refined grains with a high GI, such as white bread and pasta, are rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream.

As discussed earlier, this raises blood glucose levels; insulin is released to counter this. High insulin levels in the blood have been implicated in developing acne as it elevates IGF-1 levels.

Harley street consultant dermatologist Dr Anjali Mahto advises that “the link between acne and dairy is much weaker than the link with sugar”.

Dr Mahto suggests that for some individuals, the skin may benefit from limiting refined carbs with a high GI, such as white rice and white bread.

She adds that a healthy diet benefits your skin, so reducing sugary, refined foods certainly can’t hurt.

Key points:

- Dairy was previously associated with acne, but the evidence is weak.

- Some evidence suggests that a link between blood sugar and acne is more likely.

- Reducing refined, high GI carbohydrates helps to prevent blood sugar spikes, which may benefit the skin.

Adversely affects oral health

It’s common knowledge that sugar is bad for our teeth. The actual science behind how is more interesting.

The evidence base used to inform dentists explains how dental caries (fillings/ tooth decay) occur.

The metabolism of sugars from our diet produces organic acids, which demineralise tooth enamel.

Saliva in our mouth promotes remineralisation. Given enough time, the enamel can be completely re-mineralised.

However, if we consume sugar too frequently, there is too much acid available, and de-mineralisation dominates. This makes our teeth more vulnerable to tooth decay.

So, we should moderate how frequently we eat high-sugar foods. If we leave larger gaps between sugar consumption, our mouths have a chance to re-mineralise. What about the amount of sugar we consume at a given time?

A thorough review examining the relationship between the amount of sugar consumed and dental caries demonstrated that dental caries are less frequent when added sugar is below 10% of energy intake.

Some evidence suggests that limiting added sugar to less than 5% has even more of a benefit.

Key points:

- Dietary sugar produces acids that demineralise our tooth enamel.

- Leaving longer gaps between sugary food consumption allows saliva to remineralise the mouth.

- Tooth decay is less frequent in diets with less than 10% added sugar, and much less frequent in diets with less than 5% added sugar.

Take home message

We don’t need to eat a sugar-free diet to be healthy. But lowering sugar intake can be beneficial because sugar can have several adverse health effects, including:

- Increasing our risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Decreasing our energy levels.

- Promoting cravings for sweet food.

- Potentially increasing acne.

- Causing tooth decay.

As refined, high-sugar foods usually provide little nutritional value, the best advice is to avoid them when possible. When consuming carbohydrates, it’s best to choose real food options, such as rye bread, oats or sweet potato.

These won’t spike your blood sugar as much as refined options, such as white bread or sugary cereals, and will leave you feeling fuller for longer.